In Akira Kurosawa’s memoir, Something Like an Autobiography, he does not mention the actor Tatsuya Nakadai. This is not a slight, however, when you consider that the narrative of the memoir concludes around the time of Rashōmon (released in 1950). In the epilogue to the book, Kurosawa explains:

I am a maker of films; films are my true medium. I think to learn what became of me after Rashōmon the most reasonable procedure would be to look for me in the characters in the films I made after Rashōmon. Although human beings are incapable of talking about themselves with total honesty, it is much harder to avoid the truth while pretending to be other people. They often reveal much about themselves in a very straightforward way. I am certain that I did. There is nothing that says more about a creator than the work itself.

This book was published in 1981 (English version in 1983) between the releases of Kurosawa’s final two Samurai epics, Kagemusha (1980) and Ran (1985). And the actor he chose to embody his vision in these masterpieces was of course Tatsuya Nakadai.

He didn’t get the job as one of the Seven, but he was destined for greatness nonetheless.

It is an oft-repeated fact that Nakadai had his first film role as a wandering samurai in Kurosawa’s 1954 film Seven Samurai. As Chuck Stevens remarks in his fantastic essay on Nakadai, “those flash frames in the spotlight would prove three of the most decisive seconds in front of a camera an actor ever spent.”

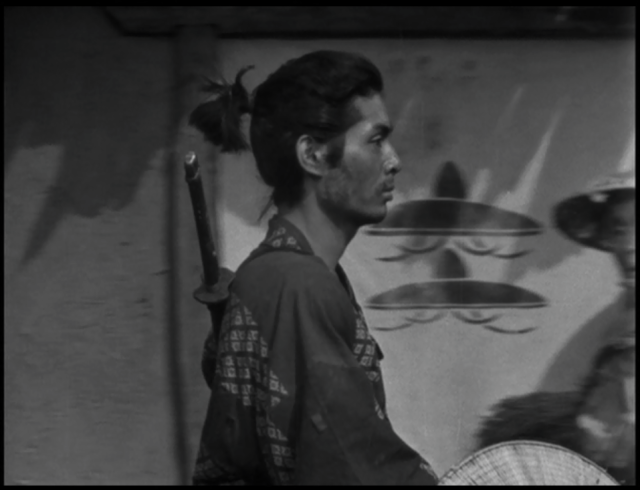

Nakadai would not appear in another Kurosawa film until 1961’s Yojimbo. In the interim, he had starred in Masaki Kobayashi’s wartime trilogy The Human Condition (one of my Blind Spot Series picks to see this year). By the time he arrived in Yojimbo, Nakadai had established himself as a chameleonic actor who was perhaps the only screen presence capable of going toe to toe with the great Toshiro Mifune. In fact, when Kurosawa went to create a sequel to Yojimbo, 1962’s Sanjuro, he turned to Nakadai again to play the antagonist. In the first film, he plays a psychotic gangster, fond of flamboyant scarves and his six-shooter. In the sequel, he is a tightly disciplined and coldly calculating head of security for a local magistrate. Yet Nakadai so completely inhabits the new role, that it probably has to be pointed out to many new viewers that they are even the same actor.

The foppish Unosuke from Yojimbo.

The proud Muroto from Sanjuro.

One of the qualities that Nakadai shared with his more famous co-star Mifune was that of an infinite adaptability. No two characters that he plays in a Kurosawa film are at all similar. The great variety of performances from these actors reflects one of the hallmarks of Kurosawa’s body of work as a whole. Kurosawa’s filmography ranges from contemporary crime dramas to the fantastic anthology of Dreams, to the Samurai swordplay chambara movies for which his is probably best known. But even within the context of a given genre, his stylistic approach is incredibly varied. From the groundbreaking “unreliable narrator” flashbacks of Rashomon to the gritty realism of the action in Seven Samurai and The Hidden Fortress to the theatrically stylized approaches in Throne of Blood or Ran, Kurosawa constantly sought to approach each story with a fresh and distinct presentation.

One of these things is not like the other…

The opening scene of Kagemusha perfectly encapsulates this mastery of diverse approaches in both direction and acting. The film opens on the candle-lit shot of Lord Shingen, his brother, and a thief. All three are dressed in identical fashion. The brother has long stood in for Lord Shingen as his body-double, and he is now proposing to train the thief for this role instead. Nakadai plays both the Lord and the thief, and instantly you can discern the difference between the two from their posture, gestures, and voice, despite their identical appearance and the distance of the camera from the subjects. Lord Shingen, sitting on a dais, is distinguished by the way Kurosawa has lit the scene so that only his shadow looms on the shiny surface of the wooden wall. The echoes of his gestures in the movements of the brother, serve to highlight the confusing similarity of the brother to the Lord, and to further distance the Lord from the thief. The undignified and rash outbursts of the thief establish a baseline for the character, which will be completely altered during the transformation he will undergo throughout the film. Later, when Lord Shingen is wounded and dying, he will be subject to uncontrolled outbursts similar to the thief’s initial demeanor, while the thief will grow in dignity and nobility as the role he plays comes to transform him internally.

No matter how furious the dramatic action or how histrionic the performances of the acting, it is clear that Kurosawa and Nakadai both are always in absolute control of the choices they are making. Nakadai’s appearance in High and Low, in which he again receives second billing to Mifune, has often been overlooked due to the low key nature of the role. Chuck Stephens wrote, “Nakadai surely recognized his relative invisibility at the lower end of the High and Low spectrum as a new kind of crossroads in his career, and quickly determined that wafting prematurely into the wings of anonymity wasn’t for him.” Nevertheless, such a dismissal of Nakadai’s performance in High and Low is an ungenerous look at both the actor and the way that Kurosawa valued him. Nakadai’s strength is such that whether he is the primary focus of the film, or a member of an ensemble cast, he is completely committed to the role. Kurosawa needed this strength to ensure that the character of Inspector Tokuro could hold together the second half of the film once the focus shifts to the police and away from the house of Mifune’s character, Gondo. Kurosawa was careful to distinguish the inspector even in the first hour of the film through careful choices of costuming and direction. When Nakadai first appears in the film as Inspector Tokuro, his character is visually distinct in that he alone is dressed in suit and tie, while all the other policemen are in shirtsleeves due to the heat. This detail also forms an immediate impression regarding the inspector’s character. He instantly strikes an air of professional confidence, reinforced by Nakadai’s performance. He is often found standing in a characteristic pose with arms folded behind his body, quietly in control despite the desperation of the scenario.

So often Mifune and Nakadai were face to face. Here they are back to back in a fantastic two shot.

During the second half of High and Low, Nakadai’s inspector delivers a clinical summary of the investigation regarding a pair of heroin addicts to a group of reporters. His speech is utterly professional, yet realistic in delivery. It contains a great deal of medical and scientific detail, establishing the absolute competence of the character. Nakadai speaks exactly as anyone would in reality, with occasional “uhs” and natural pauses. This style of line reading is in complete contrast to the performance in Ran, in which Nakadai portrays Hidetora, the King Lear analogue in Kurosawa’s loose adaptation of the Shakespeare play. As befits the theatrical origins of the story, the performance is very self conscious and exaggerated. Nakadai was no stranger to playing characters much older than his actual age, as witnessed in Masaki Kobayashi’s brilliant 1962 film Harakiri. But unlike the portrayal of a fierce and vengeful ronin in Harakiri, where he relied mostly on a display of physical anguish and weariness to make his age plausible, the central character he would play in Ran was accented with a thick application of aging makeup.

Ran is Kurosawa’s final great period piece, and the culmination of his decades long collaboration with Nakadai. Kurosawa returns here to the stylistic territory of Throne of Blood, in which the acting and costuming are much more abstracted and theatrical. If further evidence of Nakadai’s protean appearance were needed, he is described in Michael Wilmington’s essay on Ran as “the handsome Japanese superstar” whose “good looks (even tortured into Hidetora’s Noh mask of a face) fit the sense of tenuousness and impermanence that the film everywhere projects.” Chuck Stephens is more ambivalent, claiming that he was “Possessed of no more or less than his share of the sort of movie-star handsomeness upon which every leading man depends,” admitting he had a “lack in sex appeal” and referring to his “bug-eyed stare.” Certainly the intensity of his wide eyed gaze is one of the most memorable and iconic images that Kurosawa captures in Ran. Only Nakadai could have pierced through the layers of makeup to create such looks of despair at the horror which Hidetora faces.

I’ve seen things you people wouldn’t believe…

If you have seen all of Nakadai’s performances in Kurosawa films, I recommend the following as further viewing:

- Harakiri (Kobayashi)

- Sword of Doom (Okamoto)

- Samurai Rebellion (Kobayashi)

- Kill! (Okamoto)

- Every other Kurosawa that does not have Nakadai.

I will conclude this post in the only way I can, by linking you to a video of the GREATEST. DEATH. SCENE. EVER. from Sanjuro. If you have not seen the film, you owe it to yourself to watch it first, and then come back and watch this again. If you have seen Sanjuro, you know what I am talking about, and you know you want to watch it again. So here it is, Hanbei Muroto’s death in Sanjuro:

This post is part of Classic Symbiotic Collaborations: The Star-Director Blogathon, hosted by CineMaven’s Essays from the Couch. Please click the banner to enjoy other great essays about some of the classic collaborations in film history.

Great post! Kurosawa’s work with Mifune gets a lot of attention, and deservedly so, but it’s nice to read about this somewhat overshadowed collaboration. There’s a 2014 interview with Nakadai on YouTube where he talks about shooting his three-second appearance in Seven Samurai, how Kurosawa was dissatisfied with his walk and made him spend six hours getting it right. He says that it was so embarrassing that he was determined to improve so that he could “reject future offers from Mr. Kurosawa.” Fortunately, he changed his mind. I agree about the Sanjuro death scene, and I hope you enjoy The Human Condition! I think that was the first movie that really make me take notice of Nakadai. It’s definitely worth the almost-ten-hour investment, in my opinion.

LikeLike

I’m looking forward to THE HUMAN CONDITION. It will probably be a Spring Break or Summer project. I’ll look for that interview you mentioned. It’s great seeing him in all those Kurosawa documentaries on the DVDs.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Here’s the link to the interview: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_-GLkPHV1e4 The part about Seven Samurai starts around the 2:30 mark. He always gives great interviews. There’s one on Criterion’s Human Condition set, and their editions of Harakiri and When a Woman Ascends the Stairs include Nakadai interviews too. I’m not sure about any others, apart from the Kurosawas, but all of the ones I’ve seen have been fascinating and informative.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Kurosawa’s many films reach us for as many different reasons. I genuinely appreciated reading about the work of Nakadai. It is only recently I have come to appreciate his talent and versatility. Your recommendations will be taken to heart.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks for reading!

LikeLike

Whoa! That is quite some scene you posted. At first I thought my internet connection was down because the actors weren’t moving.

This is an actor and a director that I’m not overly familiar with, but I’ve been reading more about Kurosawa and his work. Your enthusiasm in this post is infectious and well researched. Thank you for sharing this with us.

LikeLike

I might actually recommend SANJURO as a starting point. There’s a lot of humor and wit, besides the action. SEVEN SAMURAI is of course the towering masterpiece, but all of Kurosawa’s films are so good, and I think very accessible to western audiences. If you don’t go on for swordplay, try HIGH AND LOW or STRAY DOG, our the heartbreakingly beautiful IKIRU.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I have seen (and absolutely love) Ikiru, but I think I’ll give Sanjuro a go, like you suggested. Thanks!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Great article. I hadn’t been much a fan of Nakadai (preferring Takahi Shimura, Toshiro Mifune, and Minoru Chiaki in Kurosawa’s stable of actors), but your essay has inspired me to take another look at Nakadai’s work. Thanks for posting your review.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yes, one of my goals in this little post was to highlight just how versatile an actor Nakadai was. It’s a quality he shares with Mifune. Both were equally strong in leading and supporting roles. Thanks for reading and for your comment!

LikeLike

Thank you, fabulous post, and you are so right BEST DEATH SCENE EVER!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks for reading!

LikeLike

This is certainly a director I mean to explore but just never get round to… where do you think is best place to start for a Kurosawa newbie? Seven Samurai is the obvious choice. I read somewhere that Kurosawa was greatly inspired by John Ford, I think I see it in the stills you selected.

Glad this blogathon led me to your blog – I look forward to reading more posts 🙂

LikeLike

Hi, and thanks for reading! You pretty much can’t go wrong with Kurosawa, truthfully.

SEVEN SAMURAI is undeniably great, but is a huge epic which might be a little forbidding if you’re not sure.

If you want to see a Samurai pic, I suggest SANJURO as a starting point, for its perfect balance of humor, action, and the straightforward fun of the narrative. THE HIDDEN FORTRESS would be my second recommendation, for similar reasons.

If you prefer a non-period drama, IKIRU is an achingly beautiful film that is one of his best.

You are correct to see Ford’s influence in Kurosawa’s work: he was a great admirer of Ford.

You have a lot of great viewing ahead of you!

LikeLiked by 1 person