Can’t write about cartoons without an anvil, right?

In 1949, the Warner Brothers cartoon studio was at their peak. They had established most of their enduring and beloved stable of characters, and were building on the legacy of legendary directors such as Bob Clampett, Tex Avery, and Frank Tashlin. The post war years saw the establishment of a more settled arrangement of working relationships in the four (reduced to three in 1947) units under the direction of Friz Freleng, Chuck Jones, Bob McKimson, and Art Davis. They still had the fantastic decade of the 50s ahead of them, but around this time sees where the comic formulas, peculiarly witty dialogue, and animation designs really crystallized into the most recognizable feeling, before suffering a very slow decline through the late 50s and into the 60s. And the biggest star of the Warner stable, capturing all of these traits in the many films he starred in, was Bugs Bunny.

After the war, America had just come through the most trying time of the 20th century, and had come out on top. During the conflict, cartoon makers had made their contributions to the war effort. Bugs Bunny sold war bonds and Daffy Duck battled the Axis leaders in WWII-era films. When the war was over, the energy and comic zeal that drove the wartime shorts was channeled into new cartoons that nevertheless still maintained a shadow of the conflict that had been left behind. Broadly speaking, the zaniness of the Clampett-directed films, and the manic energy of the Avery-directed films was toned way down as their animators found roles under Jones and McKimson. The films of this time are still, however, animated with a great deal of personality, as expressive in their own right, though without attempting the sort of lush and deliberate animation of, say Disney shorts of the 30s.

As Michael Barrier describes it in his definitive history, “Hollywood Cartoons,” this was a time when “the studio’s center of gravity shifted sharply towards its story men.” This means that story, rather than characterization, was the driving force of most of the cartoons of the post war era. The description offered here of “meat-and-potatoes Looney tunes,” by Barrier is worth quoting at length:

…fast moving, not especially elegant in drawing or design, full of blackout gags, and, most important, populated by tiny casts, usually two clearly defined characters locked in a simple, easily grasped conflict. It was during the war—itself so clear-cut a conflict—that the people making the Warner cartoons boiled most of them down to such basics. … After the war, what had become a hardened formula dominated most of the Warner cartoons.

That formula was useful in several respects. for one thing, it was economical: cartoons could be produced more efficiently with only two principal characters, especially if those characters were used in many cartoon and the animators got accustomed to drawing them. For another, a cartoon with only a few characters typically required a minimum of preliminaries: just put two characters with roughly equal capabilities, but sharply antagonistic interests, in the same cartoon, and let them have at it.

You can see exactly what Barrier is describing here through a representative sample of the Bugs Bunny cartoons from 1949, one from each directing unit. In fact, around this time, Bugs was so central to the WB program that he had to appear in at least eight cartoons a year. These cartoons were actually produced in about 1947, but due to a backlog of releases and a program of “Blue Ribbon” reissues, they were delayed in theatrical release until 1949.

Bowery Bugs (Art Davis)

Art Davis is one of the least well known of the Warner directors. He spent much of his career as an animator, and was only given his own unit for a relatively brief period of time. With wartime production demands gone, and with declining US theater attendance, Warner Bros. could not justify maintaining four cartoon units, and Davis’s was shut down in 1947. This was the last cartoon produced by the Davis unit, and the only one to star Bugs Bunny.

This rabbit’s feet won’t be good luck for you, Steve.

The Davis unit was on the bubble, but so were the writers credited with this short, Bill Scott and Lloyd Turner. Turner was asked in 1947 to either return to his earlier position as an inbetweener or to leave the studio, and he chose to quit. Supposedly, only Lloyd Turner actually wrote the story for Bowery Bugs, though both he and Scott were credited.

The credits as a whole on WB shorts are a bad indicator as to who worked on a particular short. The list of animators was rarely complete, and credits were assigned more on a rotating basis seemingly. Most famously, Mel Blanc was contractually entitled to receive the only credit for voice work in the Warner cartoons for decades. In this cartoon, Bugs’s antagonist is voiced by Billy Bletcher, probably best known for his work as Black Pete and the Big Bad Wolf for Disney, and as Spike the Dog from the Tom and Jerry shorts for MGM.

Touch your nose.

Here, Bletcher plays Steve Brody, a parody of the real life Steve Brodie, who supposedly survived a jump from the Brooklyn Bridge in 1886, made in order to win a bet. The cartoon flashes back to the Brody’s story of conflict with Bugs Bunny, when brody is on the hunt for a lucky rabbit’s foot, and decides that Bugs should be the donor. Bugs objects to that, of course, and proceeds to drive Brody nuts through a series of gimmicks involving Bugs dressed in various costumes. Everywhere Brody turns, there is Bugs tormenting him in a new disguise. When Brody has finally had enough, thinking that the whole world has turned into rabbits, he runs to the Bridge to jump for it, apparently wanting to end it all.

Note the expressionistic background, with cracks in the wall showing as Steve B. begins to crack up. Just kidding, I’m sure that is just a coincidence.

This cartoon is a solid and amusing entry in the Bugs Bunny series, but ultimately a far lesser effort than those of any of the other three directors. Art Davis didn’t have the best writers or animators, and given time he perhaps would have found as unique a voice as at least McKimson, but that was not to be. You can see the cost cutting going on in the picture as a fairly long segment is told through a series of narrated still pictures. Brody is the sort of blustering character that Yosemite Sam exemplified, but without the brilliant visual design that brings so much humor to the character. As a one-off antagonist, he is fairly forgettable. So this short remains a curiosity as the only Davis Bugs cartoon from the classic era, but not among the great uses of the character.

Bugs impersonating an officer is the last straw.

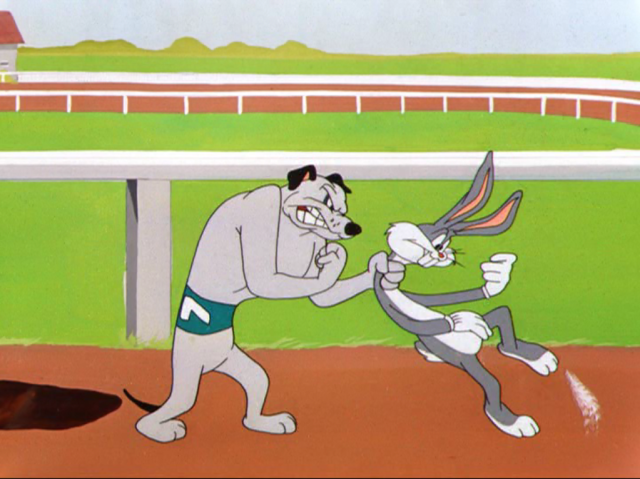

The Grey Hounded Hare (Robert McKimson)

Robert McKimson’s cartoons using Bugs released in 1949 were all a bit outside of the formula of the two-character conflict. The Windblown Hare has him pitted against the Big Bad Wolf of the fable, until he realizes that his true enemies are the Three Little Pigs, whereupon he joins forces with Big Bad to blow up the Pigs’ house of bricks. Rebel Rabbit is an extraordinary example where Bugs basically decides to make himself a menace to the entire country. It features such memorable images as Bugs sawing the state of Florida off from the country and being in the end attacked by the full might of the entire US Military. The conflict in The Grey Hounded Hare is much more typical, however, even if still outside the two-character norm, pitting Bugs against a pack of racing dogs. Another notable departure from the formula includes his battle against the black- and red-headed hillbilly pair that he defeats through square dance calling in Hillbilly Hare. But McKimson also was no stranger to creating single antagonists for Bugs according to the formula, most notably the Tasmanian Devil.

Bob McKimson was considered one of the best animators around early in his career, but as a director he has not shared the same acclaim afforded even Friz Freleng. His unit was the third fiddle to Jones’s and Freleng’s, both before and after the shut down of the fourth unit. Nevertheless, McKimson directed memorable and hilarious cartoons throughout his tenure at Warner Bros.

Pun parade.

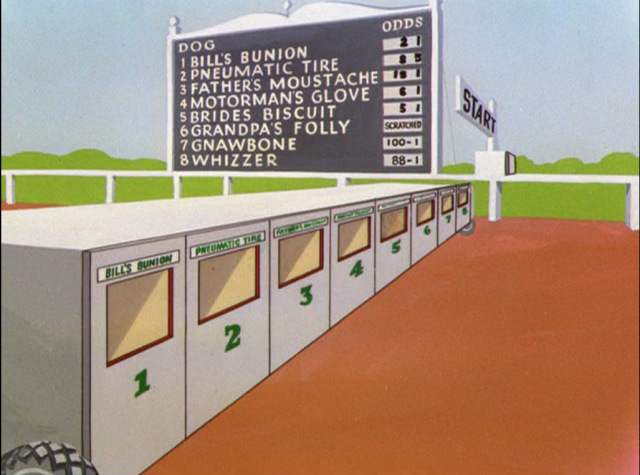

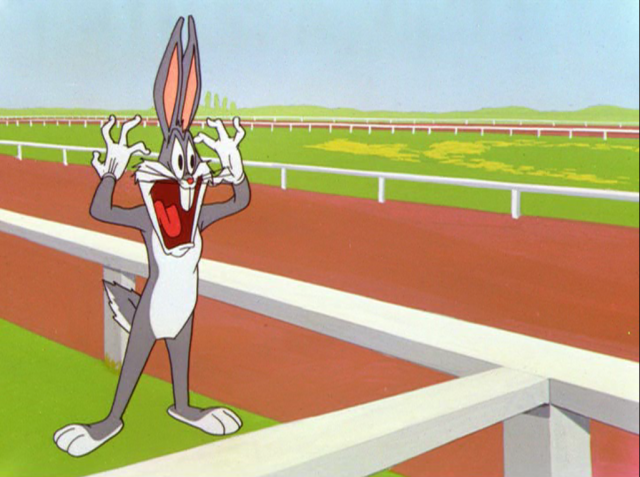

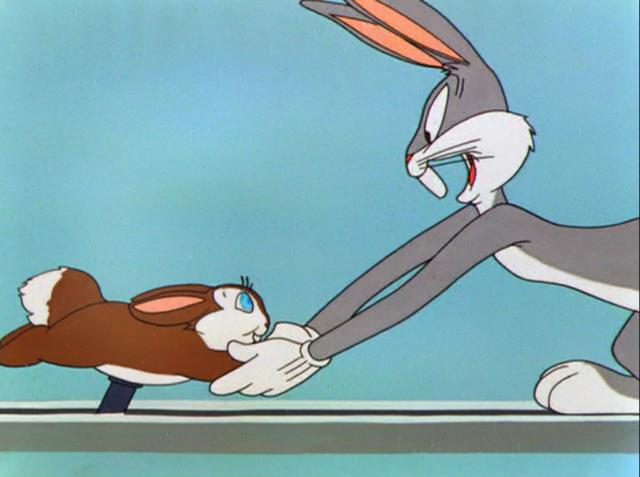

The Grey Hounded Hare finds Bugs exploring a Greyhound racetrack. Bugs is fairly disinterested until he sees the mechanical rabbit, female in appearance, that races along the railing of the track for the hounds to chase after. His sense of chivalry is ignited, and he tears down the raceway after the hounds, taking them out singly and in groups in order to save the lady rabbit. It ends with Bugs having defeated the hounds and finally caught up to the racing mechanical rabbit. When he kisses it, he receives a huge electric jolt just as it enters the box where it is housed. Undeterred, Bugs goes back for another shocking kiss – iris out.

Even as restrained a director as McKimson lets through some crazy poses here and there.

This is the most backward-looking of the four shorts here. There is a lot of reliance on a series of verbal puns for humor, which is very typical of the type of humor found in the late 30s and early 40s cartoons from WB. Each of the racing dogs is introduced in turn with names like “Bill’s Bunion (looks a little sore),” “Pneumatic Tire (rounding into shape),” and so on. Most of the cartoons made by this time had pretty much moved past this type of gag. Another, less obvious one, is a suicide gag that showed up a number of times in earlier cartoons. This involves a character, who witnessing the incredible events, exclaims “Now I’ve seen everything!” (the implication being that there’s nothing now left to live for) and then shoots themselves in the head. This occurs off screen fortunately in this short, but you can hear the track announcer make the exclamation, followed by a gunshot. This gag had long passed it’s sell-by date, but the fact that they were still using it probably exemplifies what Michael Barrier described as “the bleakness at the bottom of many of the Warner cartoons, especially the McKimson and Freleng cartoons with stories by [Warren] Foster.” This is one such cartoon, which also includes the sort of offhanded, vaguely misogynistic banter typical of the era, (“Ain’t that like a woman…”) that hasn’t aged well.

Bugs sure gets yanked around a lot.

Still, it’s overall an entertaining cartoon as well, perhaps a notch above the Davis entry, even if not a classic on the level of Rabbit Hood or High Diving Hare. It has entertaining sight gags, such as Bugs beating back the pack of dogs with the green end of a carrot, or him tricking the pack into a taxi cab before sending them away “to the dog pool.” Much of the dialogue from Bugs is fun, including some of his unique pronunciations and malapropisms. Stalling’s score quotes the old song “Baby Face” each time the mechanical rabbit comes around, but accompanied by a mechanical sounding ostinato that doesn’t quite form a harmony, punctuated with slightly off-rhythm plinks of the xylophone. In a word, the perfect musical description of the mechanical rabbit.

Wuv. Twoo wuv.

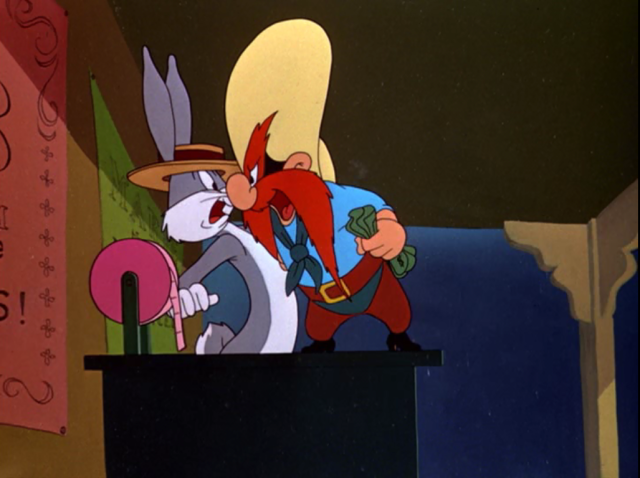

High Diving Hare (Friz Freleng)

Freleng was the most senior of the WB directors, having begun as a director for the Schlesinger studio (eventually WB) as a director in 1933. After a brief period working at MGM in the thirties, he returned to Schlesinger and continued there until 1962, when he left to form his own studio. Freleng’s films always display a sort of restrained animation, which some find over cautious, but which I find are more than offset by the pacing of the story and the brilliance of the comic timing. This one is not an exception. As in all the Bugs cartoons, much of course is owed to the voice work. Stellar voice talent, led by the master, Mel Blanc, voice of Bugs Bunny, Daffy Duck, and most of the main characters. He imbued the Bugs of this era with a sort of underlying cynicism and casual worldliness that perfectly matched the scenarios he was placed in.

Shut up and take my money!

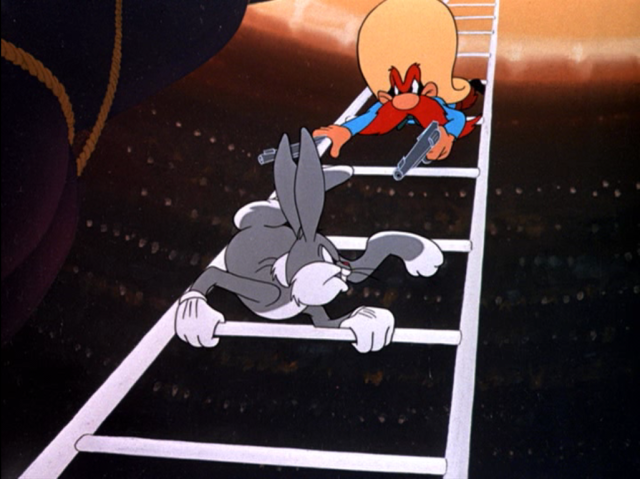

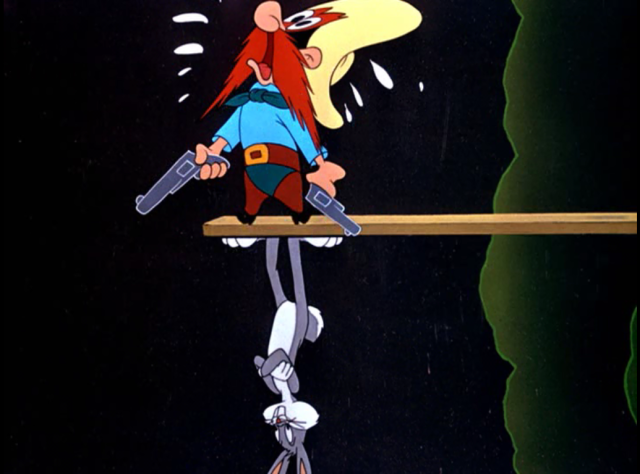

High Diving Hare is one of my favorite Bugs Bunny cartoons, and possibly the best of his conflicts with the ornery half-pint cowboy, Yosemite Sam (also voiced by Blanc). Bugs is the pitch man for a sort of old west vaudeville stage act. Sam blusters in, pulling off a whole reel of tickets to see his favorite act, “Fearless Freep,” who performs a death defying high diving act. When Bugs receives a telegram at the backstage door informing him that Freep is unable to make it to the show, he announces the cancellation to the impatient audience. Sam, however, is unsatisfied. He payed to see a high divin’ act, and he’s gonna see one. So, at gunpoint, he forces Bugs up the vertiginous ladder to jump. But Bugs is not one to meekly give in to the demands of a hothead with a gun. Through a series of increasingly improbable gags, he again and again tricks Sam into being the one to fall, sometimes into the tiny barrel of water, sometimes just crashing to the floor.

I love how Blanc delivers this line: “Quit shovin’!”

As Barrier describes it, “the gags in Freleng’s cartoons tend to be of equal weight, so that a cartoon simply stops when its time is up.” While this is probably accurate for this cartoon, it does seem to have a sort of crescendo of absurdity, climaxing with the one of the more outrageous variations on the standard Law of Gravity gag.

This has not been proven to be an effective method in altering the relative rates of two falling objects.

Another high point is Carl Stallings’ score, which alternates hilariously between heavy-handed Mickey Mousing as when Sam is racing up the ladder, and space for sound effects or even just the right amount of silence to set up the next joke. Stallings practically invented the idea of a cartoon score, and by this time in his career, he had brought it to a point of perfection. The dynamic between the score, Mel Blanc’s voice work, and Tedd Pierce’s story under the capable direction of Freleng is a real winner. This is a cartoon that I have seen dozens of times, and never fails to bring a smile to my face.

“Upside downy!”

Rabbit Hood (Chuck Jones)

Chuck Jones is undeniably the most innovative of the Warner directors going into the 1950s. His use of expressive held poses, his incredible understanding of playing to the strengths of his animators, and his willingness to push design boundaries in both characters and backgrounds all make his 1950s cartoons some of the most beloved and admired in the history of cartoons. Many, if not most of these cartoons were made with the collaboration of writer Mike Maltese. Maltese had a stong flair for gag writing, as can be seen in the endlessly inventive variations on self destruction in the Road Runner series, for example. But he also had a great talent for silly wordplay, which is brought to life so memorably in a film like Rabbit Hood, a vehicle which pits Bugs against the hapless Sheriff of Nottingham, from the Robin Hood legends.

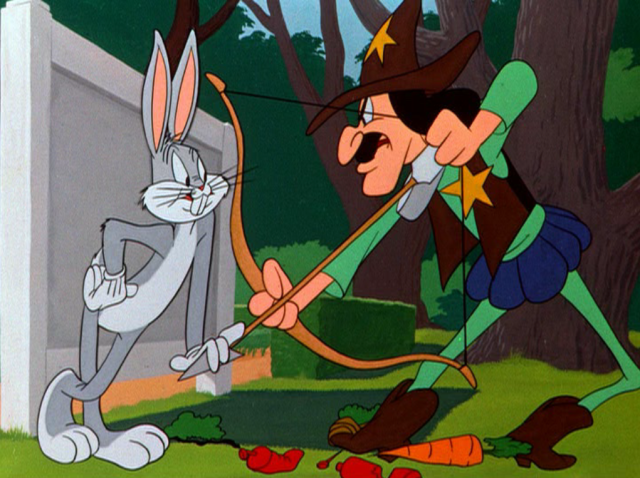

Short Shrift Sheriff

The story begins when Bugs is caught poaching a carrot from the King’s Garden, which has been fitted with alarm bells. The Sheriff appears to apprehend the thief and take him “to the rack,” but Bugs is not too concerned. A series of episodes shows Bugs outwitting the Sheriff through verbal tricks and disguises, much as he would Daffy Duck and Elmer Fudd in the “hunting trilogy” of cartoons from a few years later. My favorite gag involves Bugs convincing the Sheriff to enter the King’s Royal garden and purchase a plot of land within. Only after we see the Sheriff putting the finishing touches on the framework of a house he has begun to build, does he catch on to nature of his trickery. The Sheriff has just enough pomposity blinding his self awareness to make this gag somehow psychologically plausible, and thus hilarious.

I’ve just made a huge mistake.

As in most of these conflict-formula cartoons, the plot is really just a series of episodes, but Maltese and Jones give this one a sense of anticipation through a recurring gag. Little John, a baby-faced giant arrives twice in the cartoon to announce the arrival of Robin Hood, who of course fails to appear. Only at the conclusion of the picture does he finally arrive, with footage of Errol Flynn lifted from The Adventures of Robin Hood, to the disbelief of Bugs.

“Don’t you worry, never fear. Robin Hood will soon be here!”

Of course, he arrives only after Bugs has conclusively defeated the Sheriff, by disguising himself as the King, and bashing his head in with his scepter as he “knights” the Sheriff, in this memorable bit of dialogue:

Arise, Sir Loin of Beef!

Arise, Earl of Cloves!

Arise, Duke of Brittingham!

Arise, Baron of Munchausen!

Arise, Essence of Myrrh!…Milk of Magnesia … Quarter of Ten.

That “King” voice – I dare you not to laugh out loud at this.

As funny as many of the other Warner cartoons are, Jones’s best cartoons repay repeated viewings more than any other directors, due to the minute care put into the character animation, and the little bits of business that are easily overlooked. I will give an example, one that I only noticed for the first time in preparing to write this essay. At the moment when Bugs is trying to climb the wall to leave the area, the Sheriff appears in the remote background and fires an arrow at the rabbit, which grazes his tail end. The Sheriff’s pitifully arcing shot, which did nearly no harm, is celebrated with a little gleeful leap into the air, like that of a child who has achieved some minor success for the first time. It’s those little touches of humor that invest such richness to Rabbit Hood, and so many other of Jones’s films through the years.

It’s the little joys.

You can see a good bit of the strengths and weaknesses of each of unit through these great cartoons. The strength of the postwar Warner Bros. studio was so great that even lesser entries tend to be entertaining and rewarding of many viewings, decades after their release. Though there remain some dated contemporary topical references and attitudes, they almost always transcend the moment of their conception through the brilliant comic timing, vocal performances, and character animation. These films were made long before I was born, but I know I’ll be sharing them with my children and grandchildren until I die. Nothing has been more fun over the years and been a more consistent source of pure fun than watching the cartoons from the classic Warner Bros. studio.

This post is part of the Classic Movie Ice Cream Social, hosted by Fritzi at Movies Silently. Click on the banner below to read all the great entries celebrating fun at the movies!

I absolutely LOVE Rabbit Hood, especially the recurring joke “Don’t you worry never fear, Robin Hood will soon be here” and of course he DOES turn up at the end (I heard Warner Bros. gave Errol Flynn his own personal copy of The Adventures of Robin Hood in exchange for his permission to use that clip in the cartoon) 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

Rabbit Hood is a great one. Interesting story about Flynn. Thanks for reading!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hi Joshua. Great essay. I like the way you compared the output of the different units. I remember watching these when I was a kid and sensing that different cartoons were made by different people. Later I started noting the names in the credits. I’m glad you included “Rabbit Hood.” One of my favorites.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hi Joe, thanks for reading. Glad you enjoyed it!

LikeLike

Yes, I’m another one who likes the way you compared the different animation units and discussed the strengths of each one. This is a terrific essay on the WB cartoons, which were one of my faves as a kid. (The 7 year-old me is very happy to see High Diving Hare included in this post!)

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks so much!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Is it just me or does the Sheriff of Nottingham bear a marked resemblance to Captain Hook? (Of course, “Rabbit Hood” preceded “Peter Pan” into theaters by several years.)

LikeLike

There’s certainly a design similarity, there. The Sheriff is a much sillier character, though, given Mike Maltese’s faux-medievalv language and Mel Blanc’s dry delivery…”I ignore you.”

Thanks for reading!

LikeLike

Wondefull wrighting and nice choice of cartoons.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you very much! I appreciate the comment.

LikeLike

Great essay! I never noticed that Rabbit Hood gag, haha.

Art Davis actually had a very talented group of animators and writers, but he never took full advantage of them. Apparently he was a weak and insecure director…perhaps not the best fit for the competitive WB studio. (He did some fantastic animation for Freleng though!)

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks for reading, I appreciate the note!

LikeLike

The animation in BOWERY BUGS is solid, perhaps second in quality to Jones’s out of these 4 cherry picked cartoons. But, for me at least, it’s the story that is weak.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Some of the best cartoons every made!

LikeLike

Joshua,

Loved this article! Found you through a reference on Mike Barrier’s website and am glad I did. All of us who grew up with the WB cartoons on TV know the joy that you refer to of how rich repeated viewings can be.

thanks,

Jim

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you so much!

LikeLike