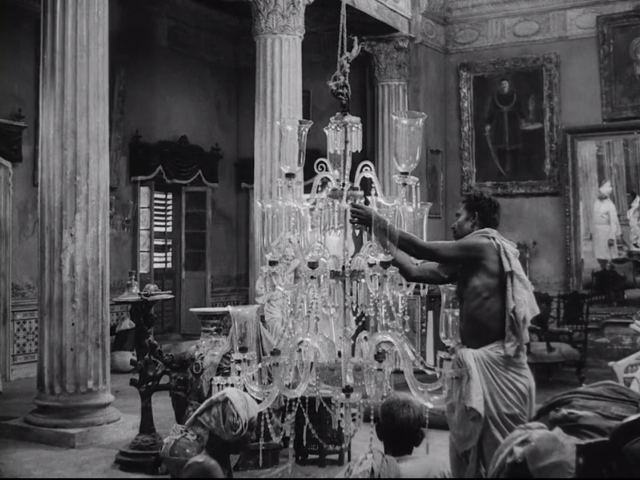

The Music Room, which dominates the fate of its master, looms large over his figure in this striking composition.

The great Indian Bengali filmmaker, Satyajit Ray, released one of his most renowned masterworks, The Music Room, in 1958, just prior to the third film in his Apu trilogy. This film, based on a short story by Tarasankar Bandyopadhyay, is in a completely different mode of storytelling than the epic and realistic style of the Apu films. Though it contains no elements of magic or mysticism, The Music Room is essentially a fable, packed with symbolism but nevertheless remaining grounded and humanistic. Mirrors, a chandelier, insects, a cane, all play a role as powerful visual symbols in Ray’s story. But the role of sound and music is most important of all, with some of the most absorbing musical performances I know of in the movies.

For a synopsis of the plot, I invite you to read Roger Ebert’s “Great Movies” review. For myself, in watching this film though I was very aware of the cultural gaps between myself and the world portrayed in the story, I still was moved by the essence of the human drama and the universal themes that Ray explored. In his essay for the Criterion release, Philip Kemp writes, “Ray himself, believing it too culturally specific to attract non-Indian audiences, ‘didn’t think it would export at all.'” Ray was mistaken, of course, since this has come to be a film beloved around the world. But still, there is some truth that there would undoubtedly be more depth of feeling if I could understand the art of the film from the inside, rather than as a foreigner.

As it happens, I think this experience of appreciation of a foreign art is one of the central ideas that Ray is laying out for us. Not foreign as in the distance between those from another culture, but as in the distance between the artist and those who merely consume the art. I use the word “consume” intentionally. Art can be appreciated, loved, experienced, admired—but in real world terms it costs money to produce, and money to procure. The distinction between patronage and vulgar consumption can be as murky at times as the distinction between the dilettante and the connoisseur.

Ray presents for us a contrast mostly between two men, the protagonist, a feudal lord whose riches have dwindled almost to nothing, and his neighbor, a newly-wealthy moneylender of low caste. Many reviews focus on the way in which the lord, Huzur Biswambhar Roy (Chhabi Biswas), is brought low through his hubris and single-minded pursuit of spending on opulent concerts in his music room. His neighbor, Mahim Ganguly (Gangapada Basu) represents the rise of the lower-caste whose riches are based on business rather than inherited lands. Mahim’s rise is reflected in his interactions with the master: his first meeting is characterized by a nervous subservience, but in their final discussion, he enters with an unmistakable swagger.

The question of whether Ray’s perspective sides with the more reserved lord, representing the feudal past, or the modern moneylender, representing a technological and capitalistic future, seems to me ultimately beside the point. While the moneylender is undeniably presented as gauche and crass, and never receives the scenes of reserved contemplation that give sympathy to the character of the lord, Ray is nevertheless certainly nor indulging in a nostalgia for the former ways of life. In the scene where lord Huzar celebrates his final triumphant concert, he drunkenly boasts to his servant of his achievement as one of his superior blood. Intriguingly, as he toasts the portraits of his noble ancestors in turn, leading up to the dramatic toast of his own portrait, he does so in English. I am not fully sure of the cultural implications of this, but the only other use of English in the film was in an early scene where the steward was reading a letter to the master describing some of his financial difficulties. There seems to be a symbolic connection between money, inherited privilege, and the unseen force of Imperial power. There is a thread of decadence between these symbolic elements, which are the very things that lead to Huzar’s downfall.

Huzar is never far from his hookah and his music.

Though Ray’s humanism leads him to portray Huzar with sympathy, he clearly does not approve of his arrogant display of wealth, symbolized to pointedly in the candlelit chandelier and lamps, which begin to ominously go out at the end of the film. But what of Huzar’s patronage of music? Huzar is very clearly a deep lover of music, and not merely interested in his concerts for the prestige of showing off his wealth. At one point, he is depicted listening to a musician play for him while he is all alone, no other audience to impress. In addition, Ray uses non-diagetic music in shots of the lord in such a way as to make it seem that this music is what he hears inside of himself. Is there a simple contrast to be made between the lord as a true and pure music lover, and the dilettante moneylender, then? Ray’s perspective is more complex than that, I believe.

The wife smiles at her son’s singing, but she cannot respect the master’s obsession.

Huzar is a bit of an amateur musician, and is shown bowing a stringed intrument in one scene while his son sings. But as he does so, he is rudely indifferent to his wife’s attempt at engaging him in conversation about the trip she is taking, one from which she will not return. He does not even look at her as he applies rosin to his bow, and tells her not to “spoil the moment.” The moneylender claims in an early scene to play a little tabla as a hobby, but is never depicted actually playing. In the final concert scene, the moneylender tries to show his enthusiasm for the dancer by offering money, but is rebuked by the lord for his manners in usurping the lord’s privilege to offer the first gift. They both have real pleasure in music, even if the lord’s is more refined and deeper. Ray does not therefore allow us to see Huzar’s character as merely a vulgar consumer of art, but ultimately his attitude towards the art of music remains greatly flawed, as the narrative makes clear.

As a musician myself, I often think about the intertwining relationships between performer and audience, and between wealth and art. Fine art is always in need of patronage, and music most of all, since it requires performance if it is to be a living art. In the Western world, the source of that patronage has moved between nobility, the church, the university, the government, the corporation, and even the individual wealthy donor. There is a definite tension between the ideal of the artist’s free expression and the demands of pleasing those with money. But patrons are not just a necessary evil; rather they are part of an ecology of giver and recipient that allows art to flourish and live.

The exquisite narrative ballet, with a hypnotic musical accompaniment.

The musicians in the film have almost no lines of dialogue. Nevertheless, they speak more eloquently than any other character in the film. Through extended concert sequences in the film’s titular music room, Ray gives space to the power of an art that transcends the ultimately futile game of one-upsmanship between the lord and the moneylender. The shape of the story seems to admit that the art needs the patronage of those with wealth, and the exquisite dancer of the final concert is shown humbly accepting the gift of money from the lord. Interestingly, this money was described by the steward as having been reserved in consecration to the divinity. The lord chose to spend it on the concert anyways. Perhaps Ray, or at least the lord, is showing us that we touch the divine in some way when we encounter music. Though his gesture was certainly mixed with his vanity, it somehow ironically reminds me of the biblical story of the widow who was commended by Jesus when she gave her last penny to God. Music, though it helps us encounter the divine, is nevertheless not itself divine, but is a creation of humanity, and therefore its experience can be polluted by the vanities of mankind.

Huzar, seen in the mirror, observes the symbolic chandelier as it is cleaned and prepared by his servants for one of his extravagant concerts.

Huzar’s wife warns that his obsession with music is an “addiction,” and indeed his life is destroyed in the familiar pattern of an addict. He sells everything he has to consume it, and of course it consumes him. I think that ultimately Ray’s sympathy is with the artists, the musicians in the story. An outsider’s love of music is not enough, if you think that transcendence of art is something that can be bought. But the musicians don’t play for free, and they have to eat too. In the first two films of the Apu trilogy, Apu’s father is a sort of poet-priest who lives in destitution, and dies in his poverty. This alone shows us Ray does not deny these material realities.

Ray’s willingness to grapple with the ironic tension between money and art is a universal quality that helps his story resonate outside of the specific cultural context that he felt would make the story only relevant to his home country. Ray’s film evoked these reflections, but in no way was didactic or moralizing. His simple fable is told with economy and cinematic beauty, with an exceptional use of music to convey his narrative forward.

My feelings after this first viewing were self-reflective. Musicians such as myself must remember not to condescend to our patrons, but to respect their place as reciprocal givers and receivers. Though their depth of feeling may be of a different kind than that of the performer, it nevertheless may be as real. And patrons must be aware of the dangers of commodifying an experience that should be accessible to people of all classes and backgrounds. If our performance is true and beautiful, then it can be meaningful to the wealthy or the poor, the noble or the common.

This post is part of the Blind Spot Series, hosted by The Matinee blog.

I stumbled across this film on Netflix I think and I found it very interesting

LikeLiked by 1 person

It’s definitely on HULU, where I saw it

LikeLike

It took me a long time to get around to The Music Room, but it was worth the wait.

I love the peculiar relationship between the 2 landowners. The old money one who is offended by the upstarts lack of taste and refinement, and whose need to assert himself leads to his destruction.

Even more interesting is the low-caste “new money” rival. Even though it is painfully evident that Roy’s best days are gone and that Ganguly is more successful now, the new man seems to need his approval. It’s a very sly statement on caste and stature.

You mentioned the great sequence at the end with the candles going out one by one. I was just gobsmacked by that when I saw this. It’s such a perfect metaphor.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yes, its a really profound film that I know will reward a revisit. As I said, a lot of the cultural details are undoubtedly lost on my superficial understanding of Indian culture, but enough is clear even for the outsider.

I was just struck at how Ray so effortlessly moved into this sort of allegorical mode, fraught with symbols, when he was previously working in this style so reminiscent of Italian neo-realism.

Thank you for reading!

LikeLike