Winsor McCay, center, in the prologue to Little Nemo.

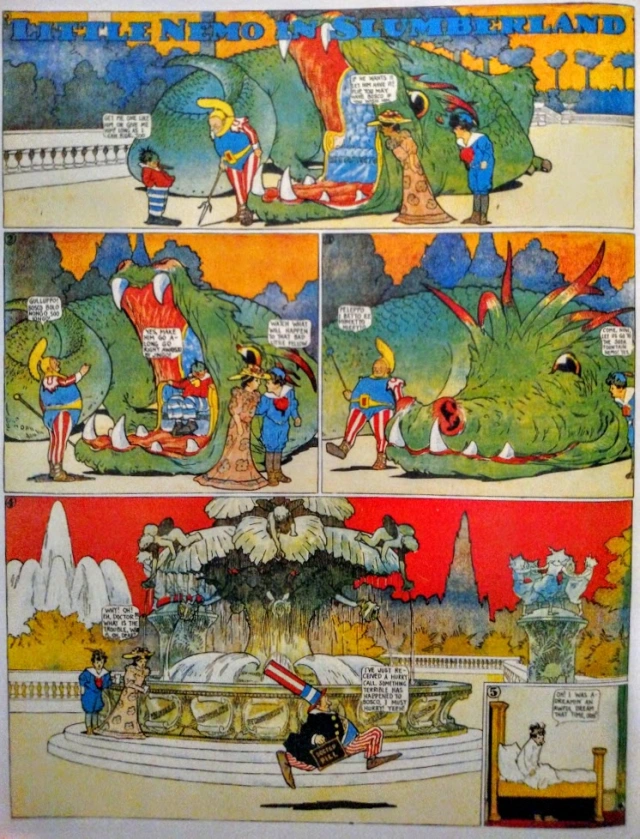

I’m willing to bet that many of my generation first discovered the work of Winsor McCay in the same way that I did: through Bill Blackbeard and Martin Williams’s important catalog of artistry known as The Smithsonian Collection of Newspaper Comics. Presented amongst dozens of other comic strip creations, both forgotten and celebrated, the full page colorful splendors of “Little Nemo in Slumberland” stood out even alongside such luminaries as Gottfredson’s “Mickey Mouse” or Segar’s “Thimble Theatre.”

Sample of Winsor McCay’s exquisite linework and fanciful colors. They quite literally don’t make them like this any more.

McCay’s drawings had an effortless draftsmanship that allowed him to depict the most whimsical fantasias, playing endlessly with both form and content of his page in a way that would never be possible for later creators crammed into a few square inches of paper. Even artists like Bill Watterson of Calvin and Hobbes fame, who fought for the creative freedom to make his vision of flexible expression in the medium a reality, would never have the freedom that the canvas of a full page provided for McCay.

Winsor McCay (1867?-1934) was not only responsible for creating some of the most popular newspaper comics of his era, but also at times was a successful vaudeville-circuit performer, where his stage act included making quick sketches for the audience. Later he also became a pioneer in the realm of animated cartoons.

I was made aware of McCay’s animation work when, in the early days of the Cartoon Network, they aired a series billed as “The 50 Greatest Cartoons,” based on the list compiled by Jerry Beck for his book of the same name. Included among the Looney Tunes and Popeyes was McCay’s most famous and endearing animated cartoon, Gertie the Dinosaur (1914). But as I was to discover, Winsor McCay created 10 known animated cartoons, each of which are astonishing for their seeming to arise sui generis, with complex and advanced understanding of the technical aspects of animation, married to the draftsmanship and whimsy that made McCay’s comics work so distinctive. Though it may be a clichéd turn of phrase, there is no one to whom the statement “ahead of his time” applies better than to McCay in the field of animation. Oscar-winning animator and McCay biographer John Canemaker points out that “fluid motion, naturalistic timing, the feeling of weight, and eventually the injection of personality traits into his characters are qualities McCay first brought to the animation medium.” McCay seems to have discovered these artistic nuances all on his own. He did this without the lengthy developmental phases and teamwork that it took, for example, the Disney studio to reach his level of sophistication in later decades.

A comparison of other animated films of the decade of the 1910s, by such studios as Bray, reveal just how advanced McCay really was. As Michael Barrier notes in his history of animation, Hollywood Cartoons,

…Bray studio films that survive from the teens tend to be fairly elaborate in drawing, like the nineteenth-century magazine cartoons they evoke, but barely serviceable as animation. Instead, a drawing may be held for many seconds on the screen or animation repeated throughout a film…

Though McCay would use the labor and time-saving techniques of cycles and repeats, his animation was nevertheless “painstakingly realistic,” in the words of Barrier.

John Canemaker has written on the connection between McCay’s depiction of subtle sequential motion in his comic strips, and the illusion of motion created in his animated films. More than just a stylistic or technical continuity exists between his work in the two media, though. McCay’s first animated experiment, though essentially plotless, was drawn from specific episodes in his long-running Little Nemo strip, and later ones were also based on his strips from Dreams of a Rarebit Fiend.

The first three films McCay made were actually created to be shown as part of his vaudeville act, and so were a sort of multimedia performance art. Animation scholar Albert Miller notes that “Later, live action prologues were added so these ‘McCay cartoons’ could be shown in movie theaters with live musical accompaniment, just like any other silent film.” While the prologue for How a Mosquito Operates has been lost, the other two are intact.

McCay’s films are still relatively little known—like most silent films, they are usually relegated to a niche interest. But they have a singular charm and vitality, and are particularly deserving of a wider audience. Fortunately today, these films can be readily seen online. For the most part, these are the creative output of a single man, (sometimes with a “couple of assistants,” according to Canemaker) and as such, are a monumental achievement not just of their time, but of any era in film history.

Little Nemo (1911)

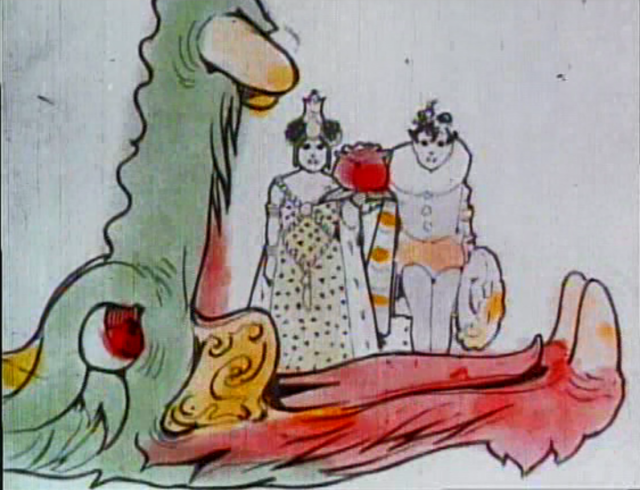

The dragon with a throne in its mouth from the Little Nemo strip appears to carry off Nemo and the princess.

The beautiful hand-colored sequences unfold, appropriately, like a set of dreamy non-sequiturs. Characters from the comic strip are transformed like in a funhouse mirror, and appear and disappear through graphical fantasies.

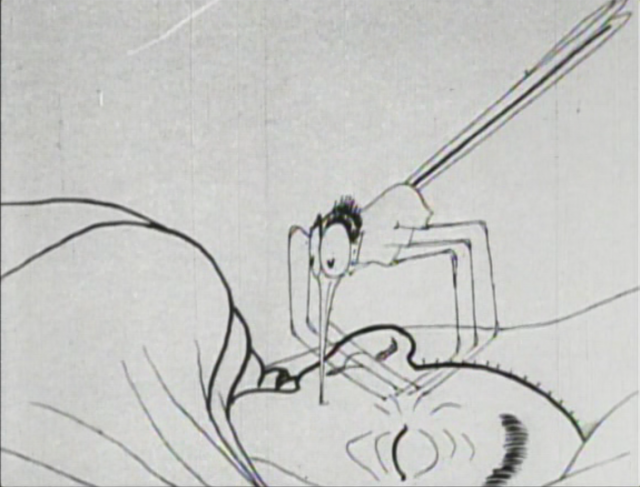

How a Mosquito Operates (1912)

Enter a caption

This film features genuinely creepy animation of the outsized mosquito feeding on a man who is trying to sleep. As Barrier describes it, “McCay animated the swelling of the enormous insect’s body, as it gorges itself on blood, with disarming subtlety: the mosquito fills out gradually and persuasively—not simply increasing in size, like a balloon filling with water, but as if its body had a certain structure, now distended.” The mosquito in fact is so ravenous that it feeds until it explodes!

Gertie the Dinosaur (1914)

Gertie meets her nemesis, the wooly mammoth.

Probably McCay’s most well-known film, Gertie is a monumental achievement, bringing to life probably the first well-realized personality animation in history. The mischievous and spunky dinosaur interacts with the animated form of McCay who acts as her trainer, as she performs a number of tricks for the audience…at least when she feels like it.

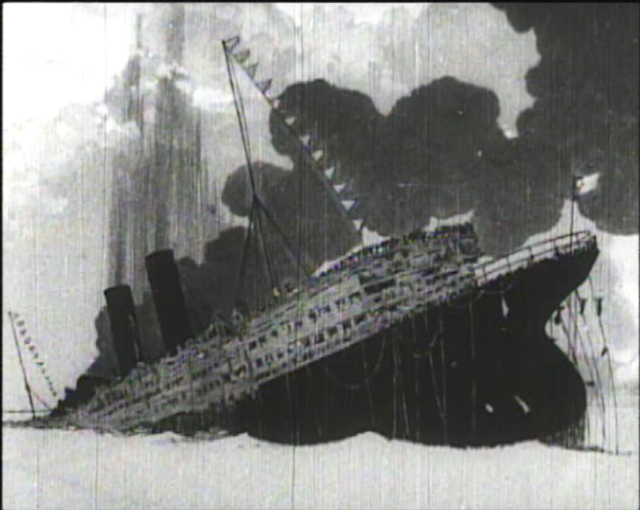

The Sinking of the Lusitania (1918)

A terrifying moment from the tragedy depicted with startling realism.

This film, a quasi-documentary account of the tragedy that contributed to America’s entry into World War I, is McCay’s masterpiece. Louise Beaudet, noted animation curator and historian, has called the film “One of the greatest animated films ever made. A profoundly moving masterpiece of propaganda, comprised of dark and powerful imagery that is ahead of its time and has rarely been surpassed.” Indeed, the horrible scenes of the passengers leaping to their doom from the sinking ship continues to resonate a century later. Prefiguring the famous scenes of the capsizing ship in James Cameron’s Titanic, the Lusitania seems to sink in real time, and the human cost is felt in stark and raw emotions.

The Centaurs (c. 1918-1921)

One can almost hear the strains of Beethoven’s Sixth…

Only fragments survive of this film, a pastoral idyll which most obviously brings to mind the similar sequence in Disney’s Fantasia, roughly 20 years later. What survives is pretty, but fairly dull, given its unfortunately incomplete state.

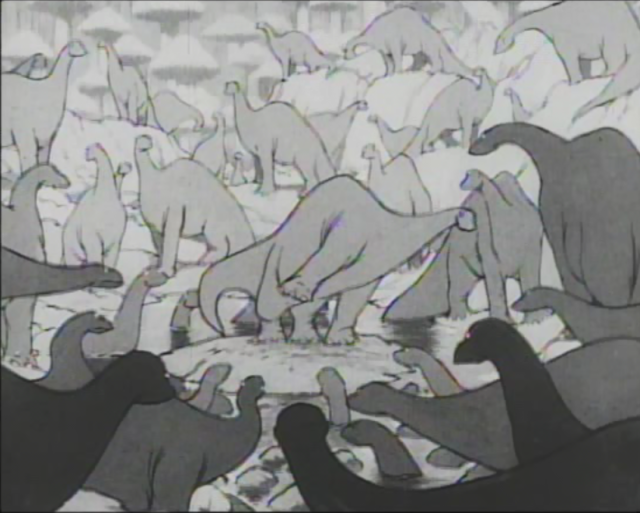

Gertie on Tour (c. 1918-1921)

Gertie is the life of the party!

This sequel to Gertie the Dinosaur also only survives in fragments, but the couple of extant minutes are as charming as the original. Gertie is spooked by a frog, then plays with a trolley, before falling into a dream where she is surrounded by dozens of her kind. The different look of this film from the original is a result of animating by painting on transparent cels photographed over a fixed background. McCay had adopted this standard technique, as opposed to line drawings on thousands of pieces of paper, beginning with the Lusitania film.

Flip’s Circus (c. 1918-1921)

Flip’s skills as an animal tamer leave something to be desired.

Little Nemo star Flip returns for a series of misadventures involving his circus act with an uncooperative hippo-like beast. This film survives as a work-in-progress. There are inserts of papers and chalk slates with indications for editing and caption cards.

Bug Vaudeville (c. 1921)

Place your bets.

In the first of the films inspired by Dreams of a Rarebit Fiend, a sleeping man has a series of visions of vaudeville acts performed by insects and spiders. While an episodic and relatively lesser effort from McCay, there is still the attention to detail and characterization that was his particular genius. Critic Andrew Sarris noted, “Only a man who knew showbiz to his bone marrow could conceive of the two bugs who pass back and forth a handkerchief with which to dry their sweaty palms before doing their hand-flips. Fellini would be honored by such insight into the ritual of performance.”

The Pet (c. 1921)

Godzilla and Kong have nothing on this King-size Canine.

Cartoonist Stephen Bissette called this film, “the first-ever ‘giant monster attacking a city’ motion picture ever made,” and so a precursor to later classics such as King Kong and Gojira, not to mention Tex Avery’s King Size Canary, which similarly posits the misadventures of house animals that begin to grow to epic proportions after eating something they shouldn’t have. The original strip that inspired this film is almost tame in comparison.

The Flying House (c. 1921)

If Rube Goldberg had worked for Henry Ford.

Finally, the last of the Rarebit films shows a man who invents a flying house, which travels almost to the moon before it is shot down by a rocket, leaving a gut-wrenching fall to earth that ends when the man and his wife wake up. A fitting and almost symbolic ending to the animation career of one of the greatest cartoonists to ever live. His work always consisted of bringing dreams to life. Like the man with the flying house, his vision was more advanced than his contemporaries in animation, and it would take many years for someone to find the ability to soar as high as he had on his own.

This post is part of the Classic Movie History Project Blogathon, hosted by Silver Screenings, Movies Silently, and Once Upon a Screen. Please follow the links to find other great posts in this series. Thanks to the authors of these blogs for hosting this great project!

Wow, awesome post! I knew about Gertie the Dinosaur, but I didn’t know there was any kind of sequel! This is so cool! 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks, there was a DVD release of these years ago, but the video quality is very low by today’s standards. (Lots of interlacing and very low resolution.) I don’t know if anyone’s tried to make an HD transfer of these films. At least you can see them on YouTube very readily today.

LikeLiked by 1 person

this is true 🙂

LikeLike

I was excited to see this post! Oddly enough, I only just heard of Winsor McCay yesterday, when I was reading a book about silent films (and the genre of silent animation) that mentioned him in passing. I watched The Sinking of the Lusitania on youtube right after and was impressed. I had not realized animation in the silent era was as sophisticated as that. Thanks for a fascinating and informative post about him and his work!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Most animation of this era really isn’t as sophisticated. Probably the only thing that approaches the fluidity of his work in the silent era is the rotoscoped animation from the Fleischer audio. But even that came along after most of this was done.

And the Lusitania picture is a truly singular achievement of the era.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Firstly, Thank You for the introduction to The Smithsonian Collection of Newspaper Comics. I had no idea. What a treasure – and so reasonably priced!

Secondly, I’m embarrassed to say I always took McCay’s innovation for granted. Until I read your essay, I didn’t fully appreciate how natural his characters’ movements are or how truly ahead of his time he was.

I loved how you catalogued these 10 films for us, and made it an easy reference for future use.

And thank you for joining the Classic Movie History Project Blogathon! I am thrilled you in particular paid tribute to Winsor McCay.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks to you for hosting. I think they made like a billion copies of that comics anthology, and it was widely distributed through some of the old mail order book clubs, so it’s not surprising that it would be available on the cheap now.

I eventually got the two volumes of the complete Little Nemo comics from Checker publications a couple years ago.

McCay is pretty great, right?

LikeLiked by 1 person

McCay is fabulous and deserves more fandom today.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I wish my learning of McCay had been with the print art you enjoyed. My introduction was on Disney’s Sunday evening TV show when I was a kid. Walt hosted an evening devoted to the history of animation and I found the entire thing fascinating, and animation still has a hold on my imagination.

A couple of years ago TCM showed a number of McCay’s films, but even now the memory is about to fade. Time for a day of immersion in the work. Now I will be a more informed viewer thanks to your most excellent article.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks for the kind words. Enjoy your rediscovery of McCay!

LikeLike

Wonderful essay, Joshua. “many of my generation first discovered the work of Winsor McCay in the same way that I did: through Bill Blackbeard and Martin Williams’s important catalog of artistry known as The Smithsonian Collection of Newspaper Comics.” I must be a member of your generation. My copy is in the closet under the stairs. I first saw “Gertie” on a Saturday night television show which promoted it all week. We’re sure lucky to be able to see what he produced, even if some of it is in fragments.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks, Joe!

LikeLike

I love Gertie. She’s a true heroine for the ages. I really enjoyed learning more about Winsor McCay’s other work, which I’m ashamed to say I wasn’t too familiar with. Thanks for sharing this fabulous post.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks for reading! No need to be ashamed, everyone has room to learn about new things.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yes, that is so true!

LikeLike

Although I’ve heard about Gertie and the Lusitania film, I haven’t seen them. I’ve always loved the 1920s, but lately the films from the 1910s have surprised me with their amazing technique. I’ll surely check out McCay’s animated films.

Don’t forget to read my contribution to the blogathon! 🙂

Cheers!

Le

http://www.criticaretro.blogspot.com

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks for reading!

LikeLike

Reblogged this on SOUND BOOKS FUN TOYS.

LikeLike