Are you now? Or have you ever been?

Dystopias never really go out of style. Since at least the early 20th century, every generation produces its fair share of dystopian literature and films. It seems that regardless of the political climate we live in, it is possible to detect the seeds of what might grow into a future where society is a frightening place. Artists seem to feel the need to express their discontent with contemporary trends through these futuristic nightmares, and readers and audiences continue to show an appetite to experience these brave new worlds. One of the earliest epic science fiction dramas was Fritz Lang’s Metropolis, a dystopic silent film that has influenced countless films since. Two of the best known novels in this mode, Orwell’s 1984, and Huxley’s Brave New World, have served as models and inspirations for many of the dystopias which followed, up to the recent Hunger Games series.

We listen and watch, even though it disturbs us.

In 1971, director George Lucas released his first feature film, THX 1138, an expansion of one of his student films from his days in the USC Film School, Electronic Labyrinth: THX 1138 4EB. This was the first film to come out of Francis Ford Coppola’s fledgling American Zoetrope studio. It was both financially and critically unsuccessful, but has been able to survive for reappraisal, thanks in no small part to Lucas’s later, unprecedented successes with the Star Wars franchise. As he had done with the Star Wars Special Editions, the 2004 DVD release prompted Lucas to make a director’s cut which incorporated a lot of new special effects, and some minor edits. And as with Star Wars, it is unfortunate that the only currently available version of THX 1138 is this revised edition. Most of the changes made stick out from the rest of the film, and are of questionable value. It is possible to see many of the changes in this video comparison.

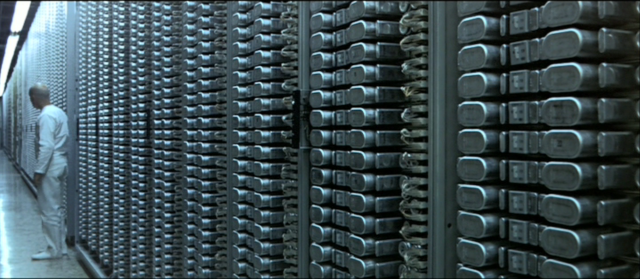

The story in THX 1138 follows many of the well established tropes in dystopian science fiction literature. Men and women no longer have names, but alphanumeric designations that are like license plate numbers. Robert Duvall plays the title character, THX 1138, who works in a factory building robots, handling dangerous radioactive material every shift. He returns home to live with his roommate, LUH 3417, played by Maggie McOmie. Everyone dresses in formless white clothing, and has a shaven head. Individuality and personal expression are impossible, as well as forbidden. As in Brave New World, the population of the society portrayed is controlled through a regular diet of sedatives. Also much like in Huxley’s novel, the structure of society is effectively that of a assembly line factory. Babies are created in a lab (we see fetuses in blue jars that prefigures the imagery from the Kaminoan clone factories in Star Wars: Episode II), and children are somehow given instruction through a chemical cocktail that they receive from IV bottles strapped to their arms. Workers are assigned a place to live, a roommate, and are given shift work producing widgets for consumption. Everything is controlled by computer and geared towards peak efficiency. Continuous messages to buy buy buy are given through PA announcements, and on holographic television programs.

The use of these holographic TV broadcasts is similar to the “seashell” earbuds and the wall-TVs in Ray Bradbury’s Fahrenheit 451. THX has nothing to do during recreational time other that view these TV programs. One that he is shown returning to and watching until LUH asks him to stop is nothing more than footage of a robot policeman beating a man who is cowering on the ground. The dull insensitivity with which THX is drawn to that program is evidence of the complete and total hold that the social structure has on individuals, as well as the complete integration and union of the entertainment, economic, and government segments. The robots that THX is shown constructing on his shifts at the factory seem to be the same ones he watched on the hologram TV, and the same ones that would soon be chasing him as a criminal. Montag, the protagonist of Fahrenheit 451 is also chased by a robot, a mechanical Hound. Bradbury’s novel famously imagines a world where books are forbidden. In THX 1138, there is no explicit mention of such a prohibition, but there are no books in the film, and no one seems interested in either reading, or the life of the mind. Like Montag’s wife, THX is preoccupied with the vapid entertainments on his television.

Literally lost in an Electronic Labyrinth.

The influence of Orwell’s 1984 can be seen throughout THX 1138 as well. Like the famous “Big Brother is watching you,” the society in Lucas’s film is used to omnipresent cameras, with unseen watchers constantly viewing everyone’s every move, and occasionally even controlling their actions remotely. Furthermore, sexual intercourse, and natural reproduction is forbidden as an aberration and a perversion. Like Winston, the hero of 1984, THX comes to an awakening of his own individuality through a sexual relationship with a female who is rebelling against the social structure. The cacophony of partial sentences in the opening montage of the film (created by brilliant sound editor Walter Murch) and the nonsensical blather on some of the television programs THX watches seem to have the same disorienting deconstruction of language that Orwell so memorably detailed in the “Newspeak” of 1984.

In borrowing these elements from Huxley, Orwell, et. al, Lucas is attempting a critique of the capitalist-consumerist culture that he and the Zoetrope filmmakers saw as a danger at the time. In the liner notes to the 2004 DVD, Lucas said that they

wanted to find artistic ways to reflect their concerns about changes in our society, about a shift away from creativity and individual achievement and toward a corporate, consumerist mentality.

So is THX 1138 merely a pastiche or an imitation of these classic works of literature? I think Lucas achieves something of an “individual achievement” despite the appropriation of ideas.

Drowning in a sea of (in)humanity.

For one thing, THX 1138 is very much a cinematic story. The themes are conveyed as much through the innovative editing and sound design as through the plot or dialogue. The direction and compositions set off the ways in which costume and production design create the feeling of the dystopia through visual means. The structure that is created is not, and could not be conveyed the same way in a novel. These cinematic elements are elevate Lucas’s creation beyond mere imitation. Even in Lucas’s weakest films, his flair for striking imagery and sound environments provide creative strengths that are fully on display in this, his first movie.

There is very little color in the world THX lives in. One of the few elements of bright color comes when THX picks up a red bauble from a room full of primary colored shapes, and then carries it home, only to place it in a trash incinerator. This is a clear, if simplistic metaphor for the meaningless goods that are produced in a consumerist society for the sole purpose of being consumed, creating a hollow and false economic cycle. The people, likewise, when they die or are killed, are referred to as having been “consumed.”

This widget is garbage.

As an audience, we are viewing the film in much the same way that the watcher characters within the film are viewing their monitors and video feeds. We consume it, in a sense, and are subtly implicated as part of the system that we are seeing critiqued. Often there is a cut from a grainy video monitor directly to the same image on film, with no intermediary. This places us in the position of the watcher, and invites us to ask ourselves in what ways our media consumption resembles the bleak visions of THX 1138‘s society.

This leads me to the the other way in which THX 1138 is somewhat unique. There is no true villain in the story. In Lucas’s later film Star Wars, which despite the mythological trappings, has a definite component of political allegory, there would be an Emperor who embodies the evil aspects of a totalitarian regime. The villain characters in Lucas’s literary models are clear: 1984 has O’Brien, Fahrenheit 451 has Chief Beatty, and Brave New World has Mustapha Mond, all who serve to articulate the guiding philosophy of the society which the protagonist has sinned against. The innovation, perhaps, of THX 1138 is that there is no such figure to stand in opposition to THX. At one point, it seems that it will be Donald Pleasence’s character, SEN 5241, who will serve as such an antagonist. But it turns out that he is also a rebel against the status quo, who has manipulated the controlling computer programs that assign jobs and living quarters for his own selfish and obscure purposes. At no point is a clear villain presented, and we are left to see the technocratic society as a whole as being the antagonist.

Could you be more … specific?

The closest thing to a crystallization of this abstract idea of a villain is the figure of OMM, a computer program functioning as a priest in phone-booth-like confessionals. The image of Christ, (taken from a late medieval painting by Hans Memling) represents OMM, who leads the penitents in a recitation of their sins, and concludes with this blessing for a dismissal:

You are a true believer. Blessings of the state, blessings of the masses. Thou art a subject of the divine, created in the image of man by the masses, for the masses. Let us be thankful we have an occupation to fill.

Work hard.

Increase production.

Prevent accidents.

And…be happy.

Everything we need to know about THX 1138’s society is in this soulless parody of a prayer. The words seem to be a blessing, but actually take the form of an advertisement. The penitent is reminded in a religious form, that they are a cog in the machine, part of the “masses.” Through the experience of THX, George Lucas is showing us his belief that the “masses,” be they business, government, or religious corporations, or a conglomerate of all of the above, are a force for dehumanization without the presence of individual freedom. Individuality, in Lucas’s vision, is the source of creativity, love, and true human happiness.

In the closing sequences of THX 1138, Lucas’s hero gradually loses all his other companions as he seeks to break free from imprisonment and prove himself a true individual. After breaking out of prison with SEN and another wanderer, he leaves first one and then the other behind until his climactic escape from the robot police who chase him. As he ascends the city structure to break out into the outside world, he is alone, a true individual, when we witness the striking final image—an extreme long shot of THX shielding his eyes against the orange blaze of the setting sun. But this is not a triumphant ending. THX has escaped, but he has lost everything and everyone to get here, and he cannot live the fully human life he has awakened to—a life of happiness through love, not consumption—on his own. His victory is hollow, and the setting sun surely represents his ultimate defeat.

The sun sets.

This post is presented as part of the Great Villain Blogathon 2017, hosted by Ruth of Silver Screenings, Karen of Shadows & Satin and Kristina of Speakeasy.

Great post. I’ve been a fan of this film ever since it popped up on TV in the 70’s (heavily edited, of course) and I stayed up late to watch it, not getting everything at that young age. I’ve seen it countless times since, and yep, should have kept the VHS copy (and a VCR) as I prefer the original cut.

Lucas’s penchant for over re-working his sci-fi stuff is really annoying here (more so than in the Star Wars flicks), as other than maybe three of the newer shots, the rest wreck the film with excess. Too many cars (those rare Ford GT 40’s were suddenly like Model T’s in the new cut), too much color, the ‘more is more’ crowd scenes (although the door opening to chaos shot makes a great first impression) and some other CGI madness change up the film and make it less… intimate (to me, at least). Ah well, at least the DVD I have has those great bonus features including the original student film.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thanks you for reading!

I agree that the one really effective update was the reveal of the crowd scene when they left the prison. The heightened contrast between the blank isolation of the prison and the insanity of the crowds makes for a great shock for both the characters and the audience. Other changes range from pointless to embarrassing. Making the Shell Dwellers at the end into cgi rat monkeys, when we had already seen one as a human little person was inexplicable.

At any rate, I don’t think that the changed ruin the film, though it would be nice if they included both versions on disc so that people could see either one, and for the purposes of preserving film history. (Something that Lucas has hypocritically campaigned for in the past.)

LikeLiked by 1 person

Oh, I think I’ve mentally blocked those cgi shell dwellers. I just went back and re-watched the film this morning and while I still dislike that scene for its changes, I still love the film as a whole. I also realized someone seeing this who hadn’t seen the original might not have a clue. Although, I got a big laugh noting that the little person in the prison kind of looks like John Belushi… or maybe that’s just my brain reminding me to not stay up so late.

LikeLiked by 1 person

He does like a Belushi mini-me, now that you mention it.

LikeLike

I’ve not seen this film, but I did check out the link you posted comparing the original film to the director’s cut. While the updated version is impressive, I agree that the original version seems more intimate. Somehow the enhancements make it feel less realistic and less distinguishable. It now looks like so many other movies.

The themes of this film, as you’ve described them, about the masses and dehumanization and constant media consumption are interesting when you consider the whole Star Wars juggernaut.

Anyway, I really enjoyed your review; in fact, here’s another of your essays that should be included as a bonus feature in a DVD or Blu-ray disk.

Thank you for joining the blogathon and for sharing this insightful review with us.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you! Your compliments are too kind. I’m just glad to get something written. It’s been really hard to find time to write lately!

LikeLiked by 1 person

I regret not seeing this movie when it was on TV during the 70s (The Late, Late Show). In any event, I still would be interested in seeing the film as it exists today. I wish Lucas could leave his old work alone and not feel it needs to be “fixed.” Doesn’t he realize he’s messing with film history? Anyway, good job here.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Well, I think it would be better served by his “director’s cut” than by a TV edit. I do recommend seeking the film out. It points to what a great experimental filmmaker Lucas is at his best, and with the right collaborators. I would love for him to return to making those kind of films, but it seems unlikely, because the creative partner is the key. In recent decades, he has seemed to want to retain all creative control, and had mostly yes men to work with rather than true collaborators. With money less of a concern, he hasn’t had to make the kind of artistic decisions that sometimes result in really creative results. That is, when money isn’t a serious limitation, you aren’t forced into being as inventive.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Agreed. Lucas needs a strong collaborator. That’s why the Raiders movies were so good.

LikeLike

This is an awesome insight. I must admit that it wasn’t the most easy movie to watch in the middle part that sagged a little but the visuals make it special.

”For one thing, THX 1138 is very much a cinematic story. ” – couldn’t agree more. It was very innovative.

By the way, there were some holograms used in the movie (the dancing hologram). Do you know any other older movies where holograms were used?

LikeLike