Zorro! Arriving in a cloud of smoke, as if summoned by the presence of injustice.

It’s hard to believe that there was a time when Zorro did not exist in the popular imagination. He seems to be as timeless a creation as his legendary English counterpart, Robin Hood, who traces his origins to ballads from the middle ages. Just under a century ago, however, the legend of Zorro was born in the 1919 serialized story “The Curse of Capistrano,” by Johnston McCulley, telling the story of the masked avenger who defends the poor and the oppressed. Almost immediately, the story was picked up for the screen by Douglas Fairbanks, and adapted into the first Zorro film, The Mark of Zorro. The film was directed by Fred Niblo, who would go on to direct other Fairbanks adventures, and also the original screen version of Ben-Hur in 1925.

The secret entrance to the Bat-cave, er…Zorro’s hideaway.

Zorro is the proto-superhero, not only for his good deeds in defending the defenseless through superior strength and skill, but for bearing all the trappings we later associate with the superhero genre. Zorro wears a mask, cape, and even false mustache, in order to disguise his true identity as the landed gentleman Don Diego. Zorro smokes a cigarillo, seemingly in order to enter in a cloud of smoke. He has a secret stall for his black horse under his villa, with a passage up to an upstairs hideout where he can resume his alter ego. Even well known tropes like the hidden entrance through a grandfather clock find their secret origin here. For the most comprehensive discussion of these elements, I refer you to the superheroic review by Steven Greydanus.

Side-eye wasn’t invented recently, you know.

In his “true” identity as the Don, he affects a foppish demeanor, constantly complaining of fatigue, and showing off childish tricks with his scarf. “Have you seen this one?” he asks to always unamused interlocutors. He has a fun recurring gag where he pulls on a string to recover his hat from anyone who takes it from him. This sense of playfulness and always being one up on those around him is the connecting link between the two personas of Don Diego and Zorro. Though Zorro is concerned with righting wrongs, and ultimately deposing the corrupt Spanish Governor and his vile military subordinates, he goes about his business with a carefree zest. He is as concerned with making a fool of his enemies as he is with defeating them.

As an example of that spirit, we see from early in the film that Zorro is not a killer, though we find out he can easily best any man or group of men in swordplay. He brands those who abuse women, poor natives, and priests with his famous “mark:” the three slashes of a Z—sometimes in their clothing, but at other times on their neck or face. The shame and humiliation of this branding—a literal loss of face—is enough to defeat those who rely on their noble blood, and the support of other nobles, in order to uphold their grip on the territory.

A priest is unjustly scourged for “treason.” Zorro will avenge this wrong.

Zorro receives what Orson Welles calls a “star entrance:” for a full reel or so of film a group of soldiers talk about him, raving about his exploits and his seemingly magical ability to appear whenever injustice is occurring. And then, just as predicted, he appears. All the buildup would be in vain if the character, as portrayed by the incredibly athletic Fairbanks, did not meet and then exceed everything that we have heard described in this prologue. In fact, the stunts in the final 20 minutes or so simply have to be seen, as they remain, almost a century later, some of the greatest ever put on film. The playful and wily Zorro leads a band of soldiers on a chase through the village, which involves climbing buildings, swinging on ropes, leaping over pigpens, disguises on top of disguises, near misses of every kind, and leaping from rooftop to rooftop. Notice that I didn’t say swordplay, because Zorro leaves behind his sword before initiating this chase: again, he is more interested in discrediting the soldiers by making fools of them, then in beating them.

Zorro’s gymnastic escape up the cart, and into the church.

There are two sword fights, however, with the primary villain of the film, Captain Ramon (Robert McKim). The Captain makes several attempts to force himself on the unwilling lady Lolita Pulido (Marguerite De La Motte). Zorro, the champion also of female honor, impresses this lady through his heroic rescues, causing her to fall in love with the mysterious vigilante. His pathetic alter ego, however, only earns her scorn for his weakness and constant fatigue. That is, of course, until the final moments of the film, when Don Diego reveals that he is, in fact, the man behind the mask, in order to best the Captain once and for all in a climactic duel—not to the death, but to the humiliation of the “mark.”

This unspoken code, that Zorro will not kill, set the example for all the superheroes to imitate. Another way that this story established a norm for future superheroes—but by a negative example—also occurs at the denouement. With Zorro’s identity revealed, the lady won, and justice established in the land, there is not much room for sequels. It seems that the trope that the hero’s secret identity must remain secret was an important part of the formula that was important for what has become the inevitable ongoing procession of serials and sequels for stories of this type. In fact, the next Fairbanks film in the series, Don Q Son of Zorro, as well as the subsequent stories by McCulley, apparently either gloss over or ignore the significance of Zorro’s revelation as Don Diego in the first story.

Nevertheless, Zorro was so popular, that he would take up his mask and cape over and over again. He lives on, not only in his superhero descendants like Batman, but in the numerous television, film and comic book stories. You can trace them all back, though to the incredible film from Douglas Fairbanks.

“Justice for All!” – a noble rallying cry for the assembled caballeros.

The film can be seen in its entirety here on YouTube, though unfortunately with no musical score. I suggest that you pick your favorite swashbuckling score and play it in the background. But no matter your choice of accompaniment, be sure to watch The Mark of Zorro:

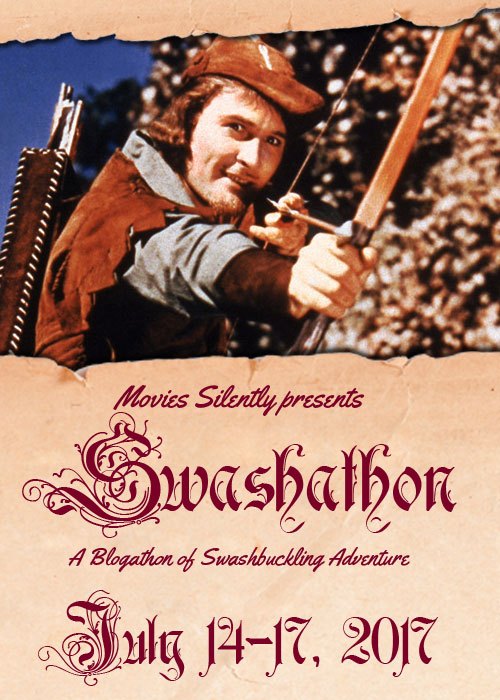

This post is part of the Swashathon! hosted by Fritzi at Movies Silently. Be sure to check out all the other entries in this Swashbuckling blogathon!

Great post! This is a very fun film and a role that is tailor made for Doug. Love the character of Zorro.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks. I enjoyed the film a lot. It was my first time to see it.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you so much! You’re right, the chase sequence near the end of the film defies description, it’s pure motion and only Doug could have done it. What a classic!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you ma’am for hosting a fine and fun blogathon!

LikeLike

Loved your review and the thoughtful points you made, including Zorro’s refusal to kill.

Also, thanks for embedding the movie! I’ll bookmark this page for later viewing.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Unfortunately it’s a pretty poor quality version on YouTube, but it’s better than nothing. Our gracious blogathon hostess has said that the best version available is the Flicker Alley “Modern Musketeer” disc.

LikeLiked by 1 person

“It’s hard to believe that there was a time when Zorro did not exist in the popular imagination. He seems to be as timeless a creation as his legendary English counterpart, Robin Hood…” Isn’t that amazing? Zorro seems like a character from ancient mythology. I’m glad you mentioned his influence on super heroes. Bob Kane, who got credit for creating Batman, said Zorro was a primary inspiration. Good review of one of my favorite Douglas Fairbanks movies.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks for reading! For more on the superhero influence, be sure to check out Steven Greydanus’s article that I linked to.

LikeLike