An attack, or playful flirting?

I had the privilege of revisiting Alfred Hitchcock’s 1941 thriller Suspicion with my daughter this week. The film is a fascinating example of Hitchcock’s work, because though it is often seen as a weaker entry in his filmography, I find it to have some of the most startling possibilities for a viewer of any of his films. Most of his films wrap up with a neat finish, whether tragic or triumphant. This one presents ambiguities that are not really resolved, right up to the final moments of the film. The film is a psychological examination of an unhealthy marriage, with an ending that is dramatically different from the novel that it was based upon. The way we interpret that ending can be quite different, however, depending on what perspective we bring to the film, as I discovered while discussing the film with my daughter after our viewing.

Suspicion is the first of four films that Cary Grant would make with the Master of Suspense. He would go on to star in my favorite Hitchcock film, Notorious, as well as To Catch a Thief, and finally North by Northwest. The story is based on the novel Before the Fact, by Francis Iles, and tells the story of a young, bookish woman named Lina (Joan Fontaine) who impetuously falls in love with gadfly, socialite, and playboy Johnnie Aysgarth (Grant). The two marry, and it soon becomes apparent that he his charm and seductive manner covers over his lack of means: his “wealth” is an appearance built out of gambling windfalls and friendly loans, and eventually theft. François Truffaut summarized the scenario, and how it differs from the source material in this way:

The novel is the story of a woman who gradually realizes that she’s married a murderer and is so much in love that she finally allows herself to be killed by him. [Hitchcock’s] picture is about a woman who, upon discovering that her husband is indifferent, a liar, and a spendthrift to boot, begins to imagine he’s a killer as well, and suspects him—though, in fact, subsequent events will prove she’s wrong—of wanting to murder her.

Keeping everyone off balance with showers of gifts.

I do believe that that interpretation is what was intended in the final version of the film. The change from Aysgarth being a murderer in fact, to being one only in the fantasy of his wife’s suspicion, was famously brought about due to the assumption that audiences simply would not accept film star Cary Grant as a murderer. For today’s viewer, who may not see Cary Grant as anything other than an actor in an old movie, that may not be an issue anymore—but more on that in a moment. In 1940s Hollywood they did not make pictures for posterity, but for the audience of the day. Hitchcock relates that during the editing process, one RKO producer insisted even on taking out anything that “gave the impression that Cary Grant was a killer.” This eviscerated version reportedly ran a “ludicrous” fifty-five minutes, and Hitch was fortunately able to restore the excised footage.

In the final scene, Aysgarth is shown driving at a reckless speed along a cliffside road, when the passenger door next to his wife flies open. She is nearly flung from the car, but Aysgarth reaches over to her…to rescue her, or to push her out? He stops the car and she gets out, and they have a final confrontation, where in a rapid verbal denouement, he gives a plausible explanation for every event that has made her suspect him of murder so far. She seems to accept this, they get in the car, and the car turns around to head back to their home. If you take it at face value, this neatly wraps up all the plot threads and clears Aysgarth (and Cary Grant) of the criminal stain of murder, if not of theft and licentiousness.

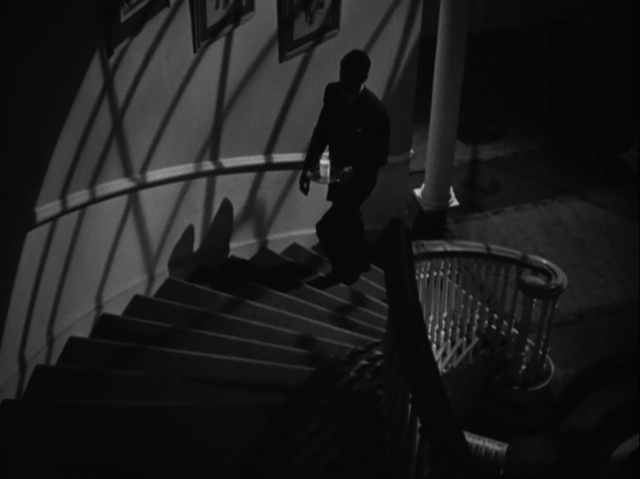

The expressionistic shadows thrown by some implausible skylight make it look like Lina is caught at the center of a spider’s web.

My daughter did not buy it, though. She not only continued to believe that Aysgarth had murdered his friend, as Lina had suspected, but that he also was also trying to kill her on the cliff side, and even (without, I think, any direct evidence in the text of the film itself) that Aysgarth had probably killed Lina’s father! I think this is a testimony to the psychological power of the editing, lighting, tight scripting, and music in the film. Franz Waxman’s score, much more overtly expressive than some others in this period of Hitchcock’s career, keenly keeps the audience focused on the highly subjective nature of the narrative. While romance is blooming, the music is a ball, but about halfway through the film, there is a stark change, matching Lina’s growing dread and paranoia. The idea to use a recurring waltz theme to indicate the change in her perception (in this case the Johann Strauss’s “Vienna Blood”), would be used again with a stronger narrative thrust in Shadow of a Doubt. Here, what begins as a symbol of their carefree romance—it’s “their song” each time they dance—morphs into a sinister theme when it is played under the famous scene where Aysgarth brings the glass of (poisoned?) milk up the stairs to her.

The spider is the milkman.

We are seeing the story very much through Lina’s perspective. When she swoons over the game of anagrams, at the sight of the word “murder,” the scene fades as well. When Lina’s father, or again when Aysgarth’s friend Beaky dies, she is not present, and so it occurs offscreen. We find out about it at a critical moment in Lina’s journey of discovering Aysgarth’s lies. She finds out from his employer that he has been fired for theft, and determines to leave him. She has written her Dear John letter, and then tears it up. She cannot bring herself to leave him, even though she now knows again just how dishonest he has been. And just at that moment, Aysgarth makes one of his frequent (and disturbing) appearances in the doorway, and comes to deliver the news of Lina’s father’s death from a heart attack.

It is easy to see how the construction of this narrative coincidence can make us start to feel that Johnnie must somehow be responsible for the father’s death. He needed money, he had reason to expect that Lina would inherit a good amount upon her father’s death, and surprise!—exactly at the moment that he need it, the father dies, also helping ensure that Lina would need the stability of her husband’s shoulder to cry on, at the moment when she was building resolve to leave him. And yet, there is no specific reason to think that he was responsible for the father’s death, other than these timing coincidences.

Right from the start, my daughter was distrustful because of the whirlwind romance that brings Lina and Johnnie together. As a father, I’m glad she disapproves. Whirlwinds are known to be bad for your health. One of their early scenes together shows them skipping church to go for a walk on a hillside. Hitchcock suddenly cuts from a shot by the churchyard to a scene on a hill where the first impression is that he is attacking her. In reality, he is helping her remove her coat, but this somewhat creepy flirtation sets the tone for the marriage and the suspected (potential) murders to come. Time after time, something capricious or sinister is uncovered, only to have Aysgarth smooth-talk his way out of the situation.

Let me save you from the danger I put you in!

And at the end, despite initial criticisms for the alteration of the plot, Hitchcock may have actually strengthened his story through the changes he made. Truffaut agreed, opining that “the film, in terms of its psychological values, has an edge over the novel because it allows for subtler nuances in the characterization.” I haven’t read the novel, so I can’t compare it directly but I can say that I think the ambiguity of the film’s ending is preferable to the intended version where Lina submits willingly to her own murder. Even if you take Aysgarth at face value, accepting his explanation as Lina appears to, it’s not a happy resolution. There is still no indication of how Aysgarth will repay the money he stole, as his supposed scheme to commit suicide using an untraceable poison, to cash in on the insurance, has been exposed. Lina may not have consented to her own murder, but she has apparently consented to something that is still terrible: a life where she can not be sure from moment to moment what is true, what is another of Aysgarth’s lies, and what is merely her own imagination running out of control. As long as she stays with Johnnie, she will forever be speeding dangerously on a cliff side, trying to keep from falling out as she hangs on for her life.

This Post is part of the “Till Death Us Do Part” Blogathon hosted by Theresa at CineMaven’s Essays From the Couch. Click the banner to read all the other great entries celebrating movies about Marriage and Murder:

This is one of my least fave Hitchcock films because the ending feels like a sell-out. I like your analysis, where you point out Lina’s uncertain future – maybe she can never really trust Johnny. Still, the whole film is set up for murder, and I think (me, who’s never written a screenplay in my life) the ending should have been more ambiguous. I don’t for a second buy Johnny’s handy “confession”, and I don’t want Lina to buy it, either. Here’s a woman who’s been seeing murder everywhere she looks, and suddenly she accepts this lame explanation? The script immediately loses credibility, in my opinion.

I quite like your daughter’s views on the film, and I’m going to keep them in mind the next time I see it.

Thanks for letting me rant. 🙂

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thanks for reading as always. I have started to think that this film is better on repeat viewings, when you know that the ending will be what it is. It allows you more freedom to explore the possible interpretations as you watch.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I like the film but for ages have felt really letdown by the ending. I share your daughters view of Grant’s character. The more I think about it now though, the more I think the ending we are stuck with actually works. It works because it’s all been about her suspicion. She was suspicious and paranoid and simply read too much into something that wasn’t there.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I agree that the ending does really work, but there is still the possibility that Lina was right all along, don’t you think?

LikeLiked by 1 person

Oh indeed, there is still that possibility for sure.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I like your analysis of the ending and how even if we accept Aysgarth’s explanations for his behavior, it doesn’t mean that their marriage and future are suddenly fine. (Personally, I’ve never been able to accept the ending at face value, and I always feel that she might be in even greater danger than ever now that he knows she’s on to him…)

LikeLiked by 1 person

Definitely a possibility, which is interesting, considering the on-the-record (yet retrospective) statement of intent from Hitchcock as to how the ending was supposed to work.

LikeLiked by 1 person

An excellent critique of a compromised movie (which most are). It’s not one I much enjoy watching. But like so many books I read as a kid and return to decades later, Hitchcock movies read very differently to me now than when I first saw them. They have become more uncomfortable. What I saw then in, say, Notorious, was the erotic connection between Grant and Bergman, great dialogue, and the film’s general stylishness. In the past decade or so Alicia’s suffering and Devlin’s cruelty and inability to connect until the last sequence have become clear, even blinding, along with Alex Sebastian’s plight—he’s not just been betrayed for his nefarious activities, he’s been betrayed in love, and so fooled twice. Same with Shadow of a Doubt. Suspicion feels unsettled in ways not entirely intentional on Hitchcock’s part. I like your and your daughter’s differing interpretations and just the fact that she watches old movies with you. Fwiw I’m more in your camp, and I agree that the “happy” ending is hardly conclusive. You’re so right that Lina will never have a peaceful moment; Johnny will keep her on her toes, dancing from skillet to stove, for the rest of her life.

LikeLiked by 1 person

A lot of great art reads differently to is as we experience it at different seasons of our lives, but Hitchcock’s best films seem to have that quality to an extreme degree!

LikeLike

Had the film ended with Joan Fontaine mailing her letter, allowing the audience to come to its own conclusions, I think this would’ve been a more successful – and satisfying – film. Those who could handle Cary Grant as a murderer would have their ending, those who couldn’t would be able to imagine that he and Joan Fontaine lived happily ever after. Though, as you note, that wasn’t very likely.

LikeLike

Suspicion used to bore me, but in the past few years it has become a favourite. It is a favourite for many of the reasons you cited. The psychological ambiguities fascinate me. I watch sometimes completely with Lina’s point of view; the next viewing will be totally different, and each time I am again drawn into that world of what is real and what is imagined.

I am very impressed that you shared this classic with your daughter and it will be interesting to see how opinions might evolve and change with subsequent viewings. I share that same relationship with my daughter, and we have opened each other’s eyes to new worlds of film.

LikeLiked by 1 person

It really does allow you to come at it in a lot of different ways!

How nice that you also can watch great movies with your daughter. It’s a great experience, isn’t it?

LikeLike

This is a fine, interesting article. I enjoyed reading it, and I look forward to reading more of your articles in the future.

By the way, I would like to invite you to join my blogathon, “The Great Breening Blogathon:” https://pureentertainmentpreservationsociety.wordpress.com/2017/09/07/extra-the-great-breening-blogathon/. It is celebrating the life and work of Joseph Breen, the enforcer of the Motion Picture Production Code between 1934 and 1954. As we honor his birthday, which is on October 14, we will be discussing and analyzing the Code era, breening films from other eras, and writing about our own ideas for classic movies. One doesn’t have to agree with the Code and Mr. Breen to enjoy that! I hope you will do me the honor of joining. We could really use your talent!

Yours Hopefully,

Tiffany Brannan

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hi Tiffany, thank you so much for your comment, and for the invitation. I apologize that I did not see it earlier than today! My life has crowded out blogging activities for several weeks.

Sincerely,

Joshua Wilson

LikeLiked by 1 person

Dear Mr. Wilson,

I understand completely. Thank you for your response. I look forward to reading more of your articles in the future.

Yours Hopefully,

Tiffany Brannan

LikeLike

I have never believed the much touted story that Hitchcock would go to the trouble of casting and making a movie about a murderer only to be blocked at every turn, forced to make an abrupt and incoherent ending.

Additionally, the book seems beneath him and trite. There were plenty of books and movies with murderers, blatantly so. And plenty of con artists marrying for money.

The movie and its ending is far superior to this rather cliched book. I am quite confident that Hitchcock made exactly what he set out to make.

LikeLike