The Terrror…er…Targets

I am watching a Roger Corman-helmed B-movie called The Terror. An elderly Boris Karloff in period costume descends stone steps in a castle to open a tomb. Another man bashes in a door to follow him. There is an appartion of a woman. A breach in the wall leads to an inrushing of water. Some characters fall into the water. A man dives in to retrieve a woman—I’m not really certain just what is occuring. The images trade in cliched horror tropes, and I feel that I have seen this movie before, even though I really never have. The opening credits are being rapidly superimposed over the fairly incoherent sequence—but they are for the wrong film. The credits proclaim that this is Peter Bogdanovich’s Targets. Though I have just begun the film, the title card comes up: “The End.”

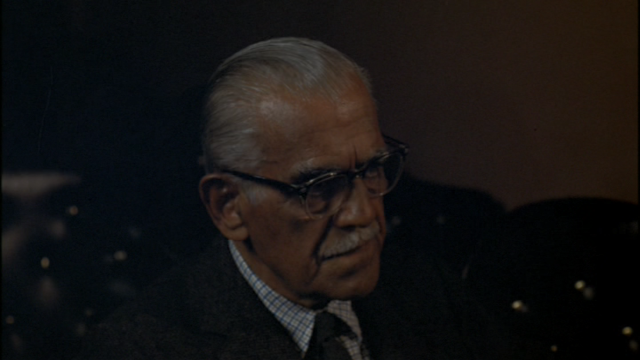

And…cut to the image of a screening room. On the front row is Boris Karloff, or as he is known in Targets, Byron Orlok. Behind him, with a characteristic head-in-hand gesture, is Peter Bogdanovich, the writer-director of Targets, playing writer-director Sammy Michaels. Cut again to a close-up of Karloff as the lights slowly come up, and with a slight twitch of the mouth, and a bowing of the head, I see that Orlok is weary, disappointed, and ready to end his acting career.

Orlok, old and tired star who is no longer scary, merely sad.

Targets, released in 1968, is Bogdanovich’s first feature film. Bogdanovich would go on to make several films that were more successful, both financially and artistically. His greatest acclaim as a director probably comes from a string of 1970s films, including The Last Picture Show, What’s Up Doc, and Paper Moon. Bogdanovich, a famous raconteur, amusingly relates the story in several places of how he came to make Targets, including on the DVD, but I first heard it on a recent episode of Gilbert Gottfried’s podcast. I highly recommend listening to this episode, which also contains many other great anecdotes about his own career and those of other great Hollywood legends.

Regarding Targets, the story goes that Karloff owed producer Roger Corman two days of work from some previous project. So Corman tasked Bogdanovich to film Karloff for two days. Then he was to gather a certain amount of existing footage of Karloff that Corman had, add the footage from the two new days of shooting, quickly shoot additional footage without Karloff, and piece it all together somehow in order to make a new film. Faced with this peculiar challenge, Bogdanovich crafted a script that featured two independent, parallel stories that come together at the denouement. They don’t quite cohere together to make a completely convincing whole, but when you consider the artistic constrictions, the result is fairly brilliant.

The first thread of the story, involves the aging actor played by Karloff, who wishes to retire from making films. His career has traveled the same path as the real Karloff, from marquee horror star of major studios, to a recognized name of bygone glory who features in a string of independent B-movies. Orlok recognizes that his brand of horror is now out-of-date, and that his career should come to a close. He is ready to quit the movies and retire. But the studios are not eager to let him go, when they feel they can still make money from his name. Bogdanvich’s director character wants Orlok to play in a new film he has scripted, and the studio heads want him to make public appearances to promote a newly completed film (the one Orlok was shown viewing in the opening credits scene). The climax of Targets will take place at a drive-in theater where Orlok has come to make such an appearance.

All-American Boy

The parallel story follows a bland young man, who lives with his wife at his parents’ home. We know almost nothing about his person, other than that he is obsessed with guns. As it happens, this film clearly has an eerie relevance to current events in 2016. The family leads a seemingly empty and shallow life, comfortably enjoying the blessings of middle-class white America, and watching TV. The man tries to talk to his wife about disturbing feelings he is having, but she doesn’t pick up on it. When at a shooting range with his father, he shocks the dad by pointing his loaded gun at him downrange. But none of this seems to clue the family in to the horror that will soon occur. One morning, the man types up a confession, murders his wife, his mother, and a delivery boy, then proceeds to go on a shooting spree. First he perches on the top of an oil refinery, and shoots at cars on the freeway. When the police begin to arrive, he escapes to hide at a drive-in theater—the very one where Orlok is making his PA. The killer will begin to shoot at people from a hole within the movie screen itself, until he drops his ammunition and is forced out into the open again.

It is not necessary to enumerate the many acts of gun violence that this film brings to mind. The basic concept and some of the details were suggested to Bogdanovich by the University of Texas sniper, who murdered people from the university’s tower in a chilling incident in August of 1966. Since the release of Targets, we have sadly had no shortage of parallel incidents in American culture.

Karloff’s character claims that his old style of horror is no longer scary, but this is really Bogdanovich’s statement that a new form of horror, grounded in everyday reality is coming into prominence. The somewhat corny old scares of fantasy monsters embodied in the clips from The Terror may indeed be old-fashioned to the audience of 1968, but in fact the depiction of homegrown gun violence in Targets is frankly dated at this point as well. Though the amount of violence shown is significant, it is shot with a restraint that would be unusual in a film on this topic today. The violence is either stylistically abstracted through the editing, as in the domestic murders, or mostly shown in extreme long shots. Targets is in the continuity of American films like Bonnie and Clyde and The Wild Bunch as an early example of bloodier gun violence, but it is decidedly on the milder end of the spectrum. It by no means approaches the blood-drenched depictions that would dominate so many films of the 1970s.

The home of a mass murderer?

The low budget which is the hallmark of a Roger Corman production is on display in the domestic scenes, where cheaply decorated interiors are shot in a style that reminds me of contemporary TV productions more than most Hollywood films. The performances of the family members, too, remind me of the vocal cadences of actors from the inoffensive and chirpy sitcoms of the 50s and 60s. While budget constraints were surely the prevailing factor, Bogdanovich seems to have used that starchy, yet comfortable artificiality to underscore the inexplicable nature of the horror that comes from a familiar, “nice” family. We don’t know where the evil that causes a man to choose to shoot up his town comes from. Targets fortunately does not try to explain it with pop-psychoanalyzing or any other means.

Despite the self-aware performance Karloff brings, he does not in real life seem to have mirrored his character’s objection to starring in low budget horror films. Though Targets was his last major American role, he continued to act until his death in 1969, even through his poor health. In the DVD intro to the film, Bogdanovich points out shots where you can see Karloff’s bowed legs which impaired his mobility. He got around with difficulty, aided by a cane and braces on both legs. He also required regular administration of oxygen due to chronic emphysema.

Bogdanovich first became known in film circles as a critic and author. He had an ongoing fascination with the directors and stars of old Hollywood films, and sought them out for interviews. His most famous association was with Orson Welles, who became a lifelong friend. It isn’t surprising that Bogdanovich made the influence of old films a major theme in the Karloff portion of the film. It’s possible that the opening transition from the clips of The Terror to the screening room is an homage to the opening of Welles’s Citizen Kane, which transitions from newsreel footage to the scene of a group of reporters watching the newsreel in a screening room.

An expressionistic moment of menace from Hawks’s The Criminal Code.

Bogdanovich also homages the famous scene in Billy Wilder’s Sunset Boulevard, where Gloria Swanson’s character Norma Desmond watches one of Swanson’s own silent pictures from her early career, Queen Kelly. In Targets, Karloff’s character Orlok is seen watching a TV broadcast of the 1931 Howard Hawks film, The Criminal Code, released the same year as Karloff’s star-defining role in Frankenstein. You can see this scene from Targets on the TCM website here. Right after the point where that clip concludes, Bogdanovich’s character laments, “All the good movies have been made.” I have been unable to see The Criminal Code, but a fascinating analysis is found at the Senses of Cinema site, including a brief discussion of the use of the film in Targets.

Quick cuts between horror star, real-life horror, and real-life star as stories converge.

While the final confrontation is, in my opinion, a bit of an anticlimax, due to the need to neatly put together the two unrelated strains of narrative, it is evocative without being prescriptive. The image of Karloff on the giant drive-in screen and the real figure of Orlok approach the shooter from opposite sides, and as the killer is confused by the double vision, Orlok strikes him with his cane and disarms him. Is there a suggestion, as Roger Ebert put it, that “the sniper can’t tell illusion from reality,” or is that too facile an interpretation? Although this would seem to be a prototypical text for exploring the theme of the potential effects of violent media in inspiring real-world violence, this does not quite seem to be on the mind of the filmmaker. For instance, we have very little evidence in the film for assigning a motive or discerning any influence of media or stories in the killer’s life. The film is not so much commenting on the influence of horror stories on reality as it is commenting on what types of stories can now seem horrifying to us, given the reality of “random” gun violence in our everyday news. Bogdanovich came up with a clever narrative way of gluing together the disparate story elements that he was charged with handling. In the process, if the results are not altogether satisfying in making a definitive statement, the film at least avoids the trap of taking a moralizing or taking a facile position on a very real plague in our society. The killer and his motivations are ciphers in Targets, but that reflects the mystery of the evil in gun violence that we remain puzzled by decades later.

At the least, this film provides a fitting meta-retrospective for the career of Boris Karloff, honoring the achievements of a long and prolific movie career that spanned from the silent era to the birth of the New Hollywood era.

This post is part of the 2016 TCM Summer Under the Stars Blogathon, hosted by Kristen Lopez of journeysinclassicfilm.com. Click the banner below to visit the roster of posts centered around classic Hollywood stars.

Hi, Joshua!

I’d like to invite you to join the At The Circus blogathon that I’m co-hosting! More details here: https://t.co/q4jTAeyGi8

Kisses!

Le

LikeLike

Thanks, I’ll give it a look!

LikeLike

wow, this sounds like an interesting film!

LikeLike

It really is. I don’t think I had heard of it before listening to the Gilbert Gottfried podcast. But the story behind it is so interesting. Bogdanovich certainly made better films, but this one is very worth seeing. Old movie buffs will find much of interest due to the sort of meta nature of the Karloff narrative, too.

LikeLiked by 1 person