“From my very first movie, what was my concentration, my inspiration, was I didn’t want to narrate something, I didn’t want to tell a story. I wanted to show something, I wanted for them to make their own story from what they were seeing.”

The final film from Abbas Kiarostami has been released into the world, and it is our job now to complete it for him. He reportedly spent several years meticulously crafting the film, and it serves as a culmination of his life’s work. I was able to make my first attempt at engaging with it recently at a screening in Houston, as part of the annual Iranian Film Festival.

Before I share the thoughts that the film inspired, I feel it necessary to make a confession of a movie-going sin, and then make an excuse for myself. When I saw this film, it was at the end of a particularly exhausting week, and I frankly had a difficult time staying awake. I found myself battling in nearly every part of it against heavy eyelids that threatened to take me into unconsciousness. I did battle, though, and I believe that I got an experience from every section of 24 Frames. It has proved an experience that I have continued to turn over in my mind in the weeks since. My justification for excusing this sin comes from Kiarostami himself. If you aren’t familiar with his opinions on watching movies, I offer these quotes in my defense:

“I absolutely don’t like the films in which the filmmakers take their viewers hostage and provoke them. I prefer the films that put their audience to sleep in the theater. I think those films are kind enough to allow you a nice nap […] Some films have made me doze off in the theater, but the same films have made me stay up at night, wake up thinking about them in the morning, and keep on thinking about them for weeks.” Source

“I’ve said that many times, and I’m not sure if it has been understood right, because very often they take that as a joke, whereas I mean it. I really think that I don’t mind people sleeping during my films, because I know that some very good films might prepare you for sleeping or falling asleep or snoozing. It’s not to be taken badly at all.” Source

Is there a significance to the 24 tree groupings?

This film has been described as a series of 24 still images that were brought to life by computer-aided animation. This, as it turns out, is partly true, like many of the stories in and behind his films. Most of the films I have seen by the late Iranian master deal, on some level, with the relationship between representation and reality, exploring the ways in which film is or isn’t able to depict an objective truth. He has played with these ideas in the labyrinthine dialogue of Certified Copy, in the meta-ending of Taste of Cherry, and through the very form of the film itself in the documentary reconstructions of Close-up.

The main difference is that in prior films, he used narrative and meta-narrative devices to pose questions on the nature of truth. The cinematic tools he used were primarily the script, editing, and the manipulation of performances by actors and non-actors in his films. In this film, a yet purer or more distilled form of cinema is in play. It is the world of silent cinema. And not even late, fully-formed silent cinema, but something like the very earliest surviving short films we have. Image and sound alone are his tools. Editing is effectively dispensed with (within each four minute scene) and there is no dialogue. So what we are left with is a drawn-out meditation on the “truth” of representational imagery itself, and its relation to time.

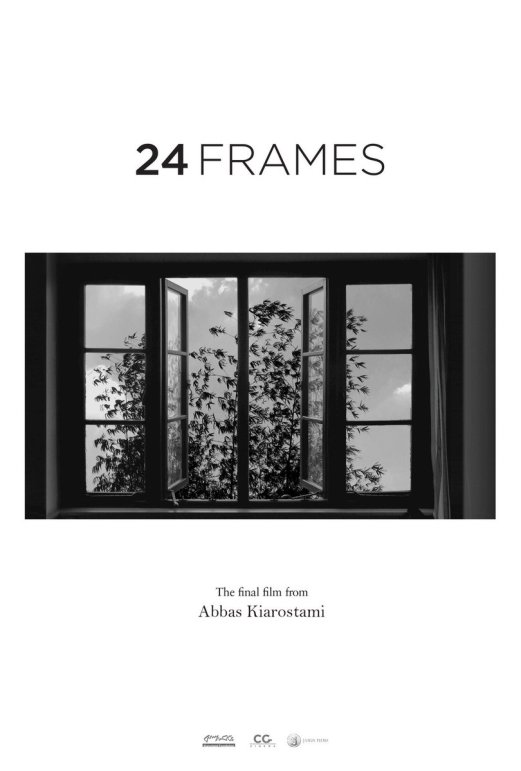

Let’s back up a bit, though. What is this film, and why is such a simple concept so hard to describe in both its particulars and in its overall effect? Well, it’s an experimental, non-narrative, pictorial film, composed of 24 mostly fixed-perspective images, assembled mostly from digitally photographed or filmed sources. These 24 “Frames” are each introduced with a title card that counts upwards and labels each segment: Frame 1, Frame 2, and so on. Preceding all of this is a title card bearing an introductory quote from Kiarostami:

I always wonder to what extent the artist aims to depict the reality of a scene. Painters capture only one frame of reality and nothing before or after it. For 24 Frames I started with a famous painting but then switched to photos I had taken through the years. I included about four and half minutes of what I imagined might have taken place before or after each image that I had captured.

Kiarostami had a notable artistic career as a still photographer as well as a filmmaker, and most of the Frames purportedly originated as photos he had taken. The first Frame, however, is a famous painting by Pieter Bruegel the Elder, The Hunters in the Snow. Kiarostami takes the liberty of creating a minimally animated version of the painting, where smoke begins to rise, snow begins to fall, and some animals begin to move about, notably the crows alighting on the branches of the tree.

The Hunters, prior to being brought to life by Kiarostami.

I think that Kiarostami’s prefatory note is indispensable in trying to form an interpretive evaluation of this film, without which it might remain an esoteric curiosity. Having seen many of his other works gives an additional, very important context to this swan song from the great artist, because you can view it as a subtle refinement or reevaluation of some of the themes he has explored in previous films. Can a single, still image capture the truth of what it depicts? After all, we do not see anything in life in that way, but always through the never-ceasing movement of time, with one moment slipping imperceptibly and inescapably into the next. When a painting or a photograph stills that time to one, composed moment, what is left out in the preceding or subsequent moments? By shifting to a motion picture, to use the term for movies that has fallen out of fashion, do we gain something that wasn’t present on the still image? Do we lose something? Is one form more “true?” How are the two art forms related, and how are they incompatible? Any possible answers to these questions are part of the story that Kiarostami asks his viewer to complete for him.

The question of truth becomes even more central in listening to this essential talk between Abbas Kiarostami’s son, Ahmad, and Godfrey Cheshire, perhaps the foremost scholar on Kiarostami working in the English language.

Ahmad helped bring his father’s final film to completion, by making some minor editorial tweaks to the Frames and their soundtracks, and by making the choices to eliminating several Frames created by Abbas in order to bring the total down to the intended number of 24. In this interview, Abbas reveals that some of the truth-bending that characterizes films like Close-up also is present even in Abbas’s description of how these images came to be conceived. Ahmad reveled that not all of them originated as photos, despite what was stated in the opening epigraph. Some were created from scratch as films to begin with. Additionally, Ahmad said that only a handful of people actually worked on the film, despite the long list in the closing credits. Most of the people listed are fictitious, many of which have humorous sounding names when pronounced in Farsi.

I have already called this a non-narrative film, but that may be, like the meaning of any of Kiarostami’s other films, open to one’s own interpretation. One of the most fundamental concepts in film is that images will convey differing meanings depending on the sequence of their ordering. There are 24 discrete Frames, each separated by a black screen and titles, and apparently given a democratic equality of screen time (I didn’t have a stopwatch to confirm it absolutely). The recurring appearance of certain animals, though, (particularly crows) lends a quasi-narrative relationship to these Frames. When the crows appear, it almost seems like Kiarostami is daring me as the viewer to see (or create) the linear relationship between the different scenes, and to recognize the recurring character of the crow from earlier Frames. When a crow is absent from a particular Frame, it paradoxically seems to strengthen the desire to create a narrative, especially upon its inevitable return in a later Frame in the series. It’s certainly possible that I was simply reading too much into this, finding a theme where only a coincidence of visual subject exists. But given the context of Kiarostami’s previous films, and his stated aims in wanting to the audience to “make their own story from what they were seeing” in those works, I don’t feel that I’m out of bounds in suggesting that he is again playing with the notion of an incomplete narrative, in a new and even more subtle formal context.

Most of the scenes in the Frames depict images of nature—trees, animals, snow. I have to call it “nature” with reservations, though. The images are composited mostly from stock footage and computer animation in order to create precisely arranged vignettes. They are in no sense a collection of mini-documentaries representing the natural world. All are artificial renditions, arranged together to satisfy the artist’s vision, just as surely as the hunters, dogs, and other elements in Breughel’s painting. This blatant artifice, which dares us to take it at face value, is one of his most persistent and profound themes as well, and has again been distilled to its most abstract and concentrated essence in this film.

Presumably Kiarostami selected 24 as the number of Frames as a reference to the 24 frames per second, which is the predominant standard rate of projecting film images. I don’t know if the number itself holds any additional significance to Kiarostami, but it seems that this title itself hints that the film is going to have film itself as the primary subject matter. In one of the Frames, the window we view has 24 panes on each side, and in another, there are 24 groupings of trees visible. This may be a coincidence, or misdirection even, as if the number is more important than what is being enumerated.

The 24th, and final, Frame contains an extraordinary vision. As it is Kiarostami’s valediction to cinema, it is indeed remarkable: he brings together a juxtoposition of elements that evokes at once many of the themes and trajectories of his work in film. A figure, seen from behind, is sleeping at a desk near an open window. Upon the desk sits a computer monitor, where we can see that frames are being rendered slowly, one at a time, from the very last shot of William Wyler’s classic film, The Best Years of our Lives. As the music of Andrew Lloyd Weber plays on the soundtrack, we see the still photographs that made up the Hollywood movie laid out one after the other, revealing the frozen photographic images underlying what we understand to produce the illusion of life when it is run at speed. The frame within a frame within a frame is an elegant visual poem that presents very simply his recurring theme of asking the viewer to question the reality of what they see. And to consider if the Copy is meaningful in a new context. Just to take the Wyler film, there are so many levels of representation we are asked to contemplate simultaneously: the original photographic frames, the film played at standard speed (not seen here but implied), the film rendered on the computer screen in the image, the film as seen in the Frame 24, and maybe even the film as rendered in the computer where Kiarostami assembled this Frame. The sleeping individual also reminds us that there is the film as “completed” or remembered in the mind of the sleeper, of us as the viewer, and of the artists who created it.

The End

24 Frames is a bold experiment that, like Akira Kurosawa’s Dreams, presents the audience with an unabashedly personal collection of visions. As with many experimental and abstract works, much of what you will take from this is what you put into it. After only one drowsy viewing, I was given many questions to ruminate upon, and I expect future viewings to open even more. As a prompt for meditation on art, truth, and beauty, this is a work of exceptional maturity and confidence I believe that it will stand as a lasting testament to the totality of Kiarostami’s work as an artist, summing up his work as a filmmaker, photographer, and poet.

For further reading on this film, I recommend Isiah Medina’s essay, and Melissa Tamminga’s review.