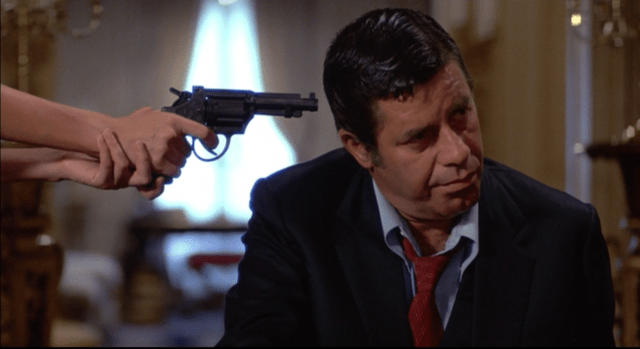

Not so nice laaaady.

Martin Scorsese has said that he did not originally want to make The King of Comedy (1983) when it was first presented to him by Robert De Niro—he “didn’t get it.” But, as he has explained in a couple of retrospective interviews, he eventually came around to understanding the script. The story follows the improbably named Rupert Pupkin (De Niro), who wished to make it big as a stand up comedian on the Jerry Langford (a brilliantly simmering Jerry Lewis) late night show. When Langford brushes off the unproven Pupkin, Pupkin’s attempts to gain Langford’s attention grow more desperate, culminating in him kidnapping Langford along with his equally obsessed and unstable friend Masha (Sandra Bernhard).

Scorsese told critic Richard Schickel (in his interview book, “Conversations with Scorsese”) that at first, he thought that it was “just a one-line gag: You won’t let me go on the show, so I’ll kidnap you and you’ll put me on the show. Hmm.” But he later began to see what De Niro saw in the script by Paul Zimmerman: the way celebrities like De Niro have to deal with “the adulation of the crowd, and the strangers who love you and have got to be with you and have got to say things.”

Rupert’s basement studio, where he perfects his act for an audience of nobody.

Let’s get this out of the way: The King of Comedy is not a comedy. Roger Ebert was right to call it “one of the most arid, painful, wounded movies I’ve ever seen.” It is indeed a very sad story, yet while Scorsese came to relate to the Jerry Lewis side of the story as a way in to the script—the side of the hounded celebrity—I think that most of us will relate to the Rupert Pupkin character. And that’s where the pain and woundedness that Ebert speaks about comes from. I grimaced at the antics of Pupkin, who desires fame and success, but doesn’t want to put in the time and do the grunt work that would allow him to climb the ranks. He wants to start at the top, on national television, without having done so much as an open-mic night at a local bar. While Simon Abrams’s Vanity Fair interview compares Pupkin to the vapidity of a Donald Trump, we can see this same impulse in everything from reality TV contestants to the desire to be the next viral video sensation. The media landscape may be very different today from the early ’80s, but people are still the same.

Seeking instant celebrity and having an idealized notion of what celebrities and their lives are really like, are two sides of the same counterfeit coin. Pupkin, like many of us, whether we admit it or not, thinks that celebrities “Don’t speak the way we speak. They’re very witty.” He conflates the glamour of what he sees on late-night TV with the reality of a star’s life. He collects celebrity autographs, but then he puts his own signature in his autograph album, in hopes of impressing a girl he knew from high school. It’s as if his mere presence among them would make his fantasy become true. And yet, Jerry Langford, the man who should have everything, lives a solitary life in a large house, tended by servants. Yeah, it’s lonely at the top, Rupert. The film plays with the audience’s understanding, too, of what is fantasy and what is real, primarily through the editing and cinematography. There are no obvious transitions to mark when we are experiencing one of Pupkin’s fantasies, and the soft-focus photography which gives an aura to the lights, is used in the same way in both the fantasy sequences and the scenes shot in an “objective” reality.

Here is an exchange from Richard Schickel’s interview, which illustrates the point:

[Schickel]: The scene where they invade Jerry’s house, I mean, honest to God, for a minute there I thought it was going to be a fantasy scene. It took me a minute to realize it was actually happening.

[Scorsese]: It’s important you say that. You know why you feel that way? Because I made a clear decision when I decided to make the picture to create no difference between the fantasies and the reality. Because if things are going on in your mind, and you can’t go to sleep, and you’re going over discussions and arguments, it’s real. It’s really happening. You can rewind. You can erase. The fantasy is real. You want to be a filmmaker, you want to be an actor, you know, it’s palpable. It’s there. It’s tangible. It’s not a ripply dissolve.

This technique of ambivalence towards the presentation of reality is carried right to the ending of the film. A news report is heard over a montage of footage celebrating Rupert’s exit from jail, his bestselling memoir, and his return to television stand-up comedy. It’s not clear whether this is supposed to be real or not. Viewing it from the perspective of the early 1980s, the elements seem exaggerated enough, presented with a satirical tone, indicating it should be Rupert’s dream. But viewed today, this ending seems to be almost plausibly realistic. Scorsese’s choice not to enforce a point of view with stylistic distinctions makes the film remain relevant as satire. The fact that the final scene is shot on video, to imitate the TV presentation, gives enough of a distancing effect. TV is “real” in the sense that it exists in the objective reality, but by its nature, anything broadcast on TV has a layer of unreality, heightening the importance of what is shown and leaving out what the camera is not intended to see.

Rupert Pupkin, ladies and gentlemen! Rupert Pupkin!

Like Uncle Rico in Napoleon Dynamite, Rupert has not outgrown his high school years. When he looks to impress someone, he looks up a woman he knew in high school, who has forgotten him. This is one of the sadly relatable parts of the film. We may not live in our mother’s basement like Rupert, but many of us don’t achieve our dreams, and feel that we just needed the right break to go our way. As Scorsese said of Rupert’s monologue at the end, “the level of the humor is…middle ground. It isn’t terrible. It’s not great. But it’s enough to get by.” That sense of mere adequacy, in the face of a daily barrage of media suggesting that only fame and perfection is valuable—that’s where the pain of the film comes.

This post is part of the Blind Spot 2017 series, hosted by Ryan McNeil at The Matinee.

I’ve been meaning to see this for a while, but now I HAVE to see this ASAP. Do you own a copy, or did you stream it online? My library doesn’t have it, and I can’t find it to stream online (on a legitimate site). Grr…

Anyway, I’ll sort all that out. Thank you for sharing this thoughtful review. When I locate a copy, I’ll be back to compare notes. 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

I borrowed the DVD from the library, but if you had to you could probably purchase the DVD cheaply. It’s a really good film, and I think underseen.

LikeLiked by 1 person