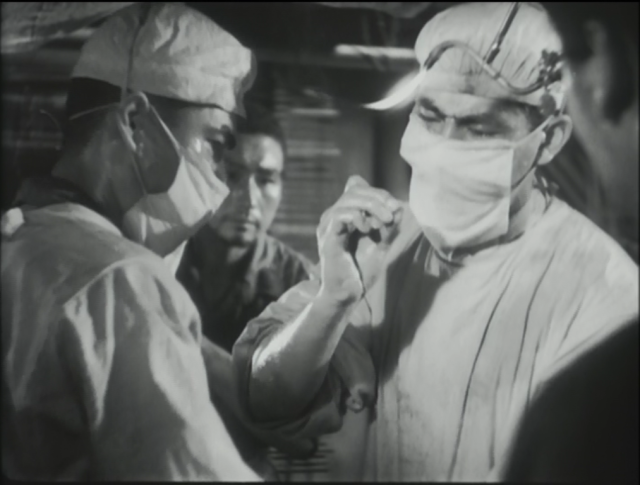

Welles as Othello, and MacLiammoir as Iago

I waited a long time to finally watch Orson Welles’s Othello, in order to see it in fully restored glory on Criterion’s new Blu-ray release. Othello is the second of three great Shakespeare adaptations that Welles created, between Macbeth and Chimes at Midnight. Whereas Macbeth was created on the low budget studio lot of Republic Pictures, and filmed rapidly in under a month, Othello was filmed almost entirely on locations in Europe and Africa, and was to take over 3 years to complete filming and post-production. Very different sets of difficulties presented themselves in making a studio picture versus an essentially guerrilla-style independent film, but the result was to be the harbinger in many ways of developments in his style that would result in films as varied as Mr. Arkadin and his later masterpieces The Trial, Touch of Evil, and Chimes at Midnight. While it does not reach the heights of that latter trio of films, it is nonetheless a worthy visual meditation on the core of Shakespeare’s great tragedy.

I say, “visual meditation,” because what is most striking about this version of Othello is not the power of the poetry (as one might expect from the gifted orator Orson Welles), but the primarily the power of the imagery. In scene after scene, Welles takes us through the emotional core of Shakespeare’s story, while taking out many of its most celebrated (and also its most controversial) lines. Despite being forced to piece together a patchwork of shots filmed literally across thousands of miles and years apart, there is a remarkable visual consistency, and a thematic unity to the black-and-white imagery. I cannot disagree with Welles scholar James Naremore, who wrote, “Of all Welles’s films, Othello is the one for which the adjective ‘beautiful’ is most justified.”

You must be logged in to post a comment.